Hip replacement surgery, or total hip arthroplasty, replaces a damaged hip joint with an artificial implant to relieve pain and restore mobility; it is most commonly done for arthritis, fractures, or bone‑death conditions and typically takes one to two hours with a recovery period measured in weeks to months.

What is a hip replacement surgery?

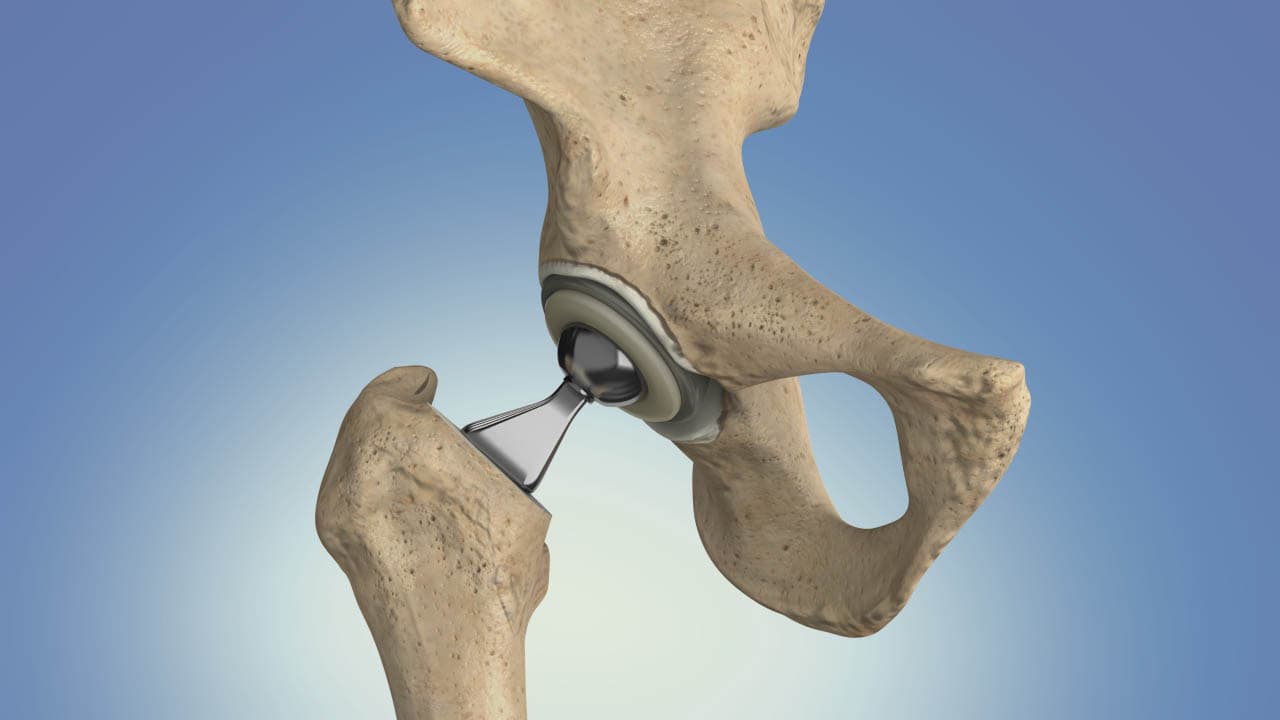

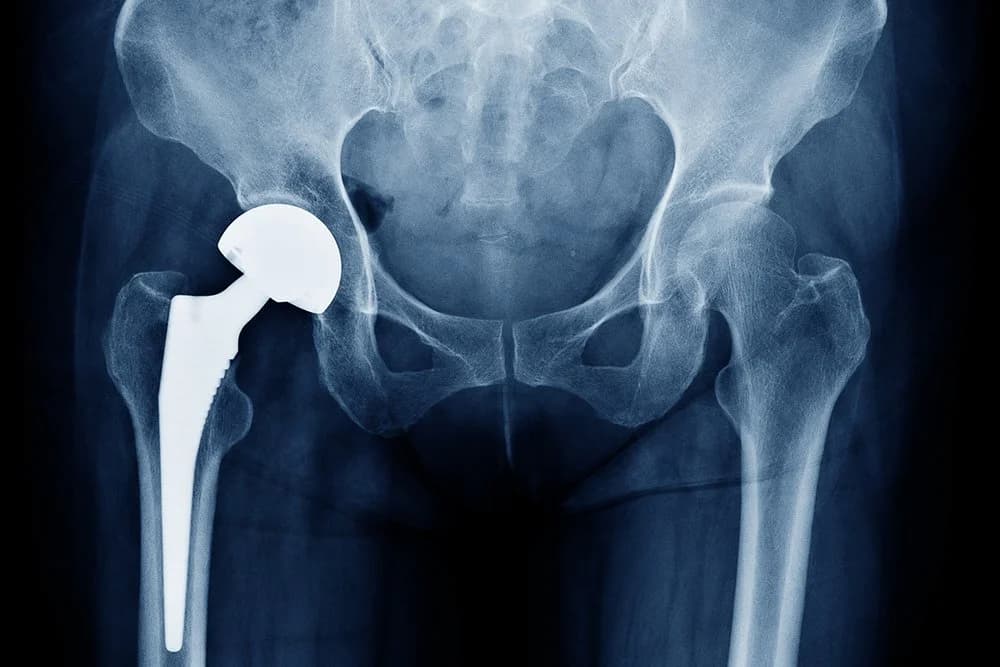

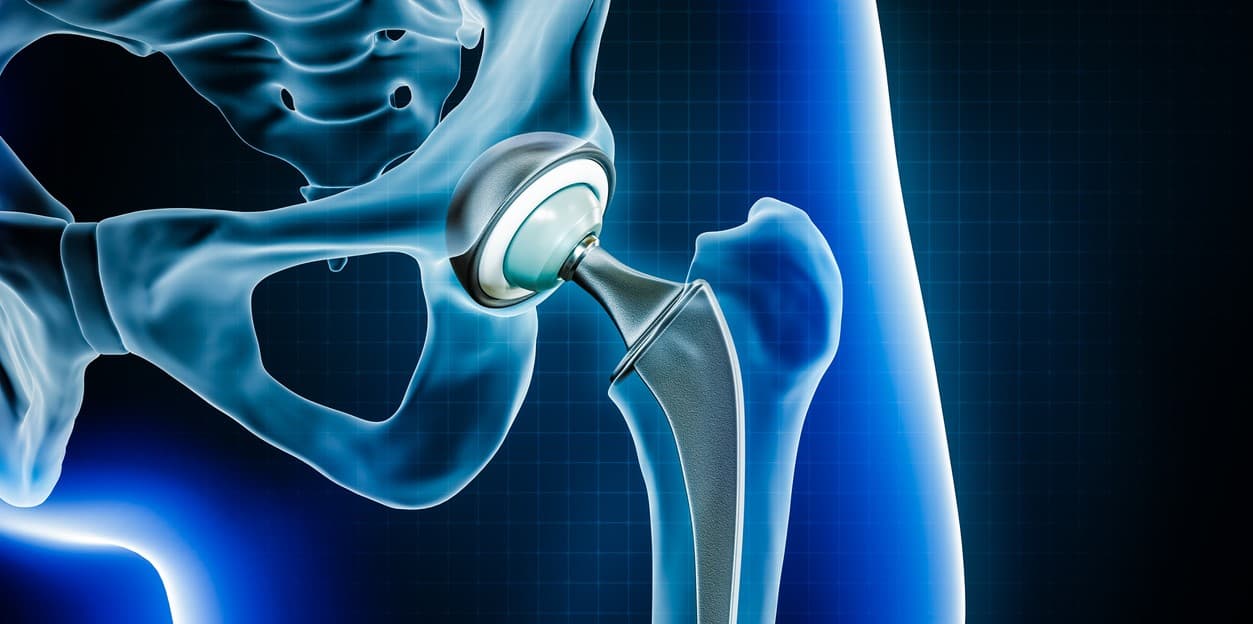

A hip replacement is a surgical procedure in which the damaged parts of the hip joint are removed and replaced with a prosthesis designed to replicate the ball‑and‑socket mechanics of a healthy hip. In a total hip arthroplasty the surgeon replaces both the femoral head (the ball) and the acetabular socket; a hemiarthroplasty replaces only the femoral head in select fracture cases. Implants are typically made from combinations of metal, ceramic, and high‑density polyethylene to provide durable, low‑friction motion. The operation is indicated when hip pain and stiffness significantly limit daily activities and conservative measures—such as medications, physical therapy, weight management, and injections—no longer provide adequate relief. Surgeons choose an approach and fixation method (cemented, uncemented, or hybrid) based on patient age, bone quality, and activity level; uncemented components rely on bone ingrowth into a porous surface, while cemented components are fixed with bone cement. The procedure usually takes one to two hours under regional or general anesthesia, and most patients begin mobilizing with physical therapy within 24 hours. Modern hip replacements can last many years, often 15 years or more, but implant longevity depends on activity, implant type, and surgical technique.

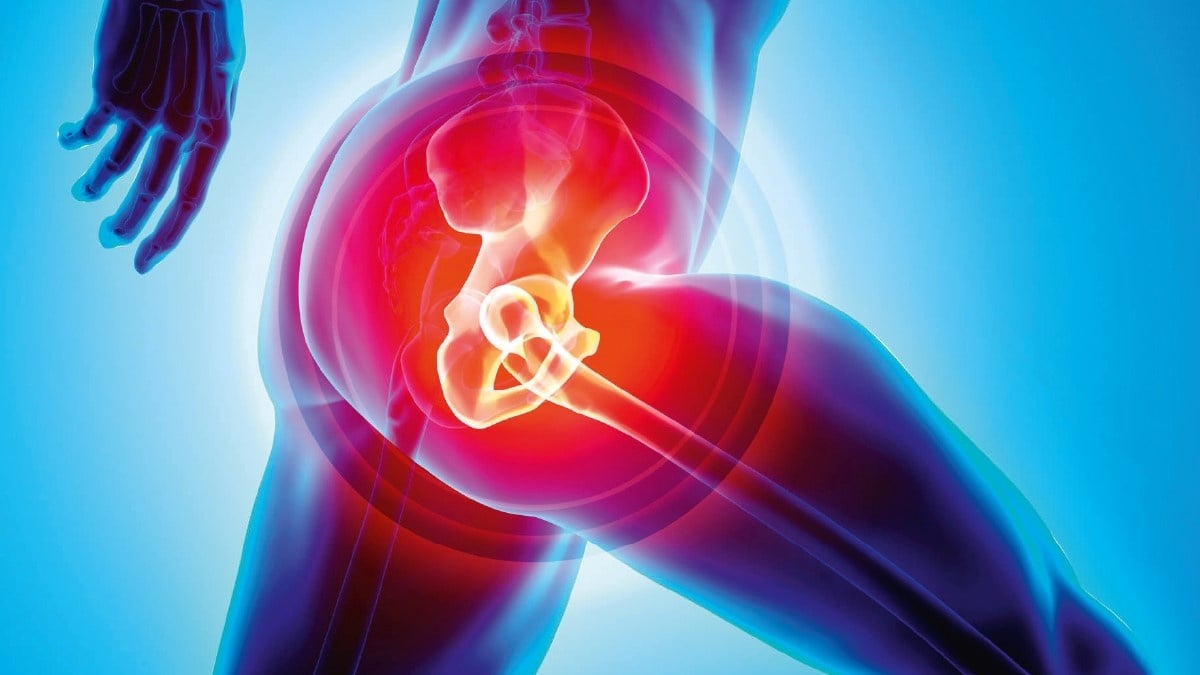

Why Do People Need Hip Replacement?

People need a hip replacement primarily because the hip joint has become so damaged that everyday activities are painful or impossible and non‑surgical treatments no longer provide relief. The most common cause is osteoarthritis, a wear‑and‑tear condition that erodes cartilage and leads to bone‑on‑bone pain, stiffness, and loss of function; when pain limits walking, sleeping, or self‑care despite medications, physical therapy, weight management, and injections, surgeons may recommend total hip arthroplasty to restore comfort and mobility. Other inflammatory or structural conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and hip dysplasia can progressively damage the joint and prompt replacement to prevent disability. Osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis), where loss of blood supply causes bone collapse, is another indication because it can rapidly destroy the femoral head and produce severe pain that is unlikely to improve without surgery. In older adults or when the hip is shattered by trauma, complex fractures may be best treated with a hip replacement rather than fixation, especially if the bone quality is poor or the fracture pattern compromises joint integrity. The decision also weighs patient factors—age, activity level, overall health, and goals—because modern implants can provide durable pain relief and functional gains for many years, improving quality of life and reducing reliance on pain medications. Key considerations before surgery include realistic expectations about recovery, potential risks (infection, blood clots, dislocation), and the fact that replacement is typically reserved for cases where conservative care has failed to restore acceptable function. Overall, hip replacement is chosen when the benefits of substantial pain reduction and improved mobility outweigh surgical risks and when it offers the best chance to return the person to meaningful daily activities.

What are the different types of hip replacement surgery?

A total hip replacement (total hip arthroplasty) replaces both the femoral head (ball) and the acetabular socket with prosthetic components and is the most common option for end‑stage arthritis because it reliably relieves pain and restores function; implants may be cemented, uncemented, or hybrid depending on bone quality and surgeon preference.

A partial hip replacement (hemiarthroplasty) replaces only the femoral head and is frequently used for certain displaced femoral‑neck fractures in older, lower‑demand patients where the socket remains healthy; it is a shorter operation with different long‑term wear considerations than total replacement.

Hip resurfacing preserves more native bone by capping the femoral head with a metal surface and pairing it with a metal socket; it has been offered to younger, active patients who want to conserve bone for potential future revisions, but it carries specific risks and is less commonly used today.

Hip revision surgery addresses failed or worn primary implants—due to loosening, infection, instability, or fracture—and often requires more complex reconstruction, bone grafting, and specialized implants to restore stability and leg length.

Minimally invasive and muscle‑sparing approaches describe surgical exposures rather than implant types; they aim to reduce soft‑tissue trauma and speed early recovery but require surgeon experience and do not change the fundamental implant choices or long‑term outcomes.

What are the types of hip replacement approaches?

The two main surgical exposures for hip replacement are the posterior approach (incision at the back of the hip) and the anterior approach (incision at the front); each has distinct technical steps, recovery patterns, and trade‑offs, and the best choice depends on patient anatomy, surgeon experience, and goals.

The posterior approach accesses the hip from the back, giving surgeons excellent visualization of the joint and wide exposure for implant placement. It has been the traditional and most commonly used method for decades and is familiar to many surgeons, which can translate into reliable implant positioning and reproducible results. The approach typically involves detaching and later repairing short external rotator muscles and the posterior capsule; when repaired carefully, long‑term outcomes are excellent, though historically this approach has been associated with a slightly higher early dislocation risk if soft tissues are not adequately repaired.

The direct anterior approach (DAA) uses an incision at the front of the hip and is described as muscle‑sparing because it works between natural tissue planes rather than cutting major muscles. Advocates report faster early recovery, less initial pain, and earlier return to function in some patients, since the approach can reduce early soft‑tissue trauma. However, the anterior approach has a learning curve, requires specific operating room setup and instruments, and may have different complication profiles (for example, wound issues or nerve irritation) that depend on surgeon experience.

Hip replacement surgery recovery process

An effective recovery after hip replacement typically starts in the hospital where nurses and physiotherapists help the patient sit up, stand, and take the first steps—often within the first 24 hours—using a walker or crutches while pain is managed with medications and local measures such as ice and elevation. Early movement reduces the risk of blood clots and helps restore function; most patients can go home when they can safely walk a short distance, manage basic self‑care, and have a stable wound. In the first two weeks expect pain, swelling, and limited mobility, which are controlled with prescribed analgesics, wound care instructions, and a scrotal‑support–style equivalent for the hip (supportive clothing or dressings). Over 2–6 weeks many people resume light daily activities and transition from assistive devices to a cane or no aid, while formal physical therapy focuses on gait training, range of motion, and strengthening the hip and core. By 6–12 weeks most patients report substantial pain relief and improved walking tolerance, though full recovery—returning to higher‑impact activities and maximal strength—can take several months; long‑term follow‑up monitors implant function and screens for complications such as infection, dislocation, or implant loosening.

What type of hip replacement implant is best?

Choosing the best hip replacement implant depends on individual goals and biology rather than a universal winner. Modern implants combine a femoral stem, a ball (head), and an acetabular liner or cup, and are made from metal, ceramic, and high‑density polyethylene in various pairings to balance wear resistance, strength, and biocompatibility. For many patients metal‑on‑polyethylene and ceramic‑on‑polyethylene bearings offer a reliable mix of durability and low wear, making them common first‑line choices because they perform well across ages and activity levels. Ceramic‑on‑ceramic bearings have very low wear but carry a small risk of squeaking and are chosen selectively for younger, active patients who prioritize longevity. Hip resurfacing preserves more bone and can suit some younger men with good bone quality, but it has fallen out of favor for many because of specific metal‑related risks and fracture concerns. Fixation method—cemented, uncemented, or hybrid—is equally important: uncemented implants rely on bone ingrowth and are often preferred in younger patients with good bone, while cemented stems may be better for older patients with poor bone quality. Ultimately, the best implant is the one that matches your anatomy, lifestyle, and long‑term plan, chosen in partnership with an experienced surgeon.

Conclusion

Different types of hip replacement surgery offer tailored solutions—total, partial, resurfacing, and revision procedures, plus minimally invasive approaches—so the best option depends on the patient’s age, bone quality, activity goals, and the surgeon’s experience.

Read More