Radiation therapy (radiotherapy) uses high‑energy radiation to damage cancer cell DNA, shrinking tumors or killing cancer cells locally; it can be delivered externally or internally and is often combined with surgery, chemotherapy, or systemic therapies to improve outcomes.

What is radiation therapy (radiotherapy)?

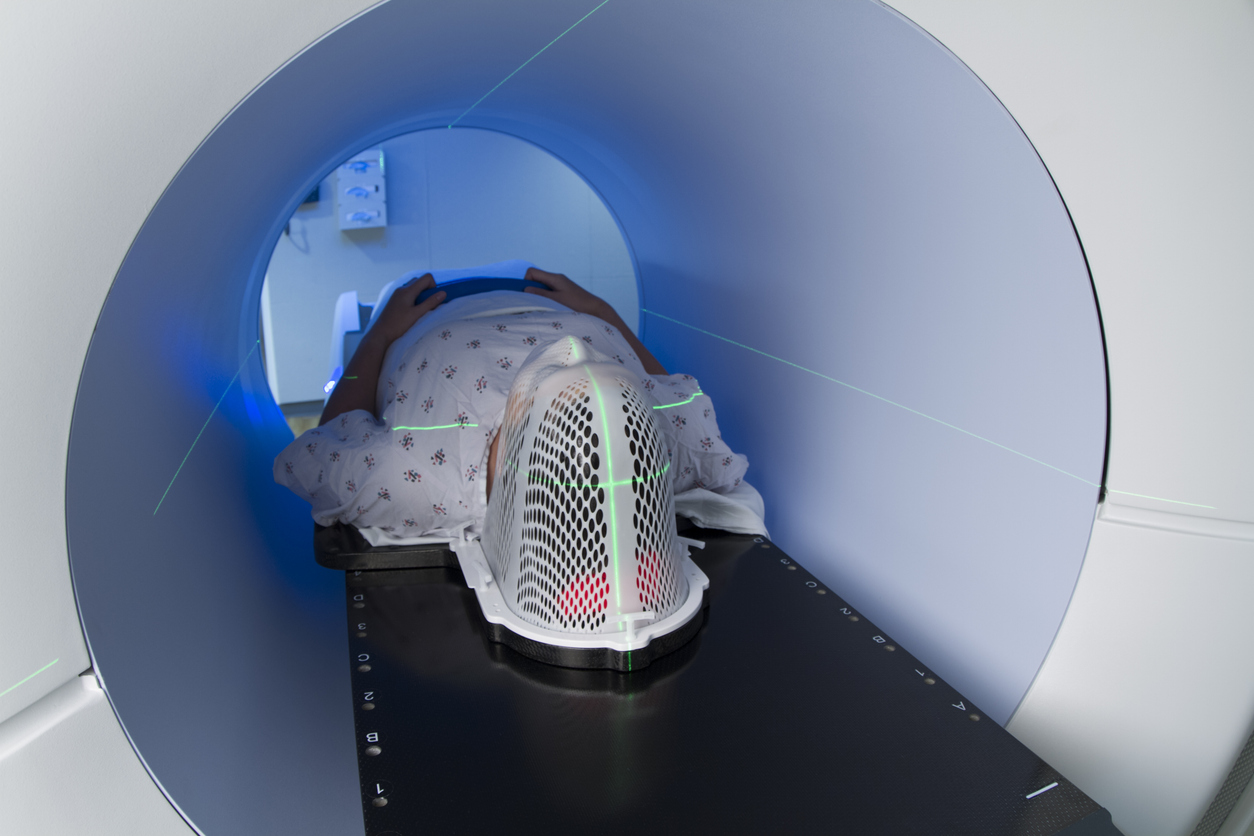

Radiation therapy, often called radiotherapy, is a medical treatment that uses ionizing radiation—such as x‑rays, gamma rays, electron beams, or protons—to destroy or control cancer cells by causing DNA damage that prevents cells from dividing and surviving. It is a local or regional modality, meaning it targets a specific area of the body rather than circulating systemically, and it can be delivered externally from a machine (external beam radiation) or internally by placing radioactive sources near or inside the tumor (brachytherapy); systemic radiopharmaceuticals deliver radioactive drugs through the bloodstream for certain cancers. Treatments are given in fractions—small daily doses over days to weeks—to maximize tumor cell kill while allowing normal tissues time to repair, and advanced techniques such as intensity‑modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), and proton therapy improve dose precision and reduce exposure to nearby organs. Radiation may be used with curative intent, as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy around surgery, or palliatively to relieve pain, bleeding, or obstruction in advanced disease, and its role is determined by tumor type, location, stage, and patient goals.

What are the types of radiation therapy?

Radiation therapy includes two main approaches: External beam radiation therapy (EBRT), which directs high‑energy beams from outside the body to a tumor, and internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy), which places radioactive sources inside or next to the cancer to deliver a high local dose while sparing surrounding tissue.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) delivers ionizing radiation from a machine outside the body and is the most commonly used form of radiotherapy. Modern EBRT techniques include intensity‑modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), stereotactic radiosurgery and stereotactic body radiotherapy (SRS/SBRT), and proton therapy, each improving dose conformity to the tumor and reducing exposure to nearby organs. Treatments are planned with CT, MRI, or PET imaging and delivered in fractions—small daily doses over days to weeks—to maximize tumor control while allowing normal tissue repair. EBRT is versatile and used for curative, neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative purposes across many tumor sites.

Internal radiation therapy, or brachytherapy, places radioactive sources directly into or next to the tumor, enabling a very high radiation dose to the cancer with rapid dose falloff to surrounding tissues. Brachytherapy can be low‑dose rate (LDR) or high‑dose rate (HDR) and delivered as intracavitary (within a body cavity) or interstitial (implanted into tissue) treatments. It is commonly used for cervical, prostate, gynecologic, and some head and neck cancers, and is often combined with EBRT or surgery to improve local control. Because the source is close to the tumor, treatment times can be short and side effects localized, but careful planning and imaging are essential to position sources and protect critical structures.

A third, less localized approach uses systemic radiopharmaceuticals—radioactive drugs given by mouth or injection that travel through the bloodstream to target cancer cells (for example radioiodine for thyroid cancer or radiolabeled agents for metastatic bone or neuroendocrine tumors). These agents provide a targeted systemic radiation effect and are selected when disease is widespread or when a molecular target is available.

How is radiation therapy used for cancer treatment?

Radiation therapy is applied in multiple clinical roles depending on the cancer type, stage, and patient goals: as a curative modality when it can eradicate a localized tumor, neoadjuvant treatment to shrink a mass before surgery, adjuvant therapy to lower the risk of local recurrence after an operation, or palliative therapy to relieve pain, bleeding, or obstruction from advanced disease. Treatments are tailored using detailed imaging and multidisciplinary planning so that external beam radiation (EBRT), brachytherapy (internal sources), or systemic radiopharmaceuticals deliver the appropriate dose to the tumor while sparing nearby organs. Radiation is given in fractions—small daily doses over days to weeks—to increase cancer cell kill and allow normal tissues to repair; stereotactic techniques (SRS/SBRT) and intensity‑modulated approaches concentrate higher doses precisely for small targets, while brachytherapy places sources directly into or next to tumors for very high local dose. Radiation is often combined with surgery, chemotherapy, targeted agents, or immunotherapy to improve outcomes: for example, chemoradiation can increase cure rates in certain head and neck, lung, and cervical cancers, and postoperative radiation reduces local recurrence risk in many solid tumors. Throughout treatment, clinicians monitor response with imaging and manage acute and late side effects that are usually localized to the treated area.

What cancers are treated with radiation therapy?

Radiation is a versatile local and regional treatment applied across a wide spectrum of malignancies. It is commonly used for breast cancer (after lumpectomy to reduce local recurrence and sometimes after mastectomy), prostate cancer (as a primary curative option or postoperatively), and lung cancer (for early-stage tumors with curative intent and for symptom control in advanced disease). Head and neck cancers frequently rely on radiation either alone or combined with chemotherapy to preserve organs and function, while cervical and other gynecologic cancers often use brachytherapy to deliver very high local doses. Radiation is central to the management of central nervous system tumors (primary brain tumors and brain metastases) and is a key tool for treating bone metastases, spinal cord compression, and painful or obstructive metastatic lesions to provide rapid symptom relief. Some cancers—such as testicular seminoma and certain lymphomas—are particularly radiosensitive and may be cured or controlled with radiation as a mainstay of therapy. Brachytherapy is commonly used for prostate, cervical, and some gynecologic and head and neck tumors because it concentrates dose within the tumor while limiting exposure to nearby organs. In addition, systemic radiopharmaceuticals (radioactive drugs) treat diseases like differentiated thyroid cancer (radioiodine) and certain metastatic bone or neuroendocrine tumors, offering a targeted systemic radiation approach when disease is widespread. The choice to use radiation depends on tumor type, stage, location, prior treatments, and patient goals; multidisciplinary teams tailor modality (external beam, stereotactic, brachytherapy, or radiopharmaceutical), dose, and fractionation to maximize tumor control and minimize side effects. Because radiation can both cure localized disease and rapidly palliate symptoms from advanced cancers, it remains a cornerstone of cancer care across many diagnoses.

What are radiation therapy side effects?

Radiation side effects arise because nearby healthy cells are exposed while the tumor is targeted, so most patients experience fatigue and localized reactions such as skin redness, irritation, or breakdown in the beam path; when the head and neck is treated, patients often develop mucositis, sore throat, dry mouth (xerostomia), taste changes, and difficulty swallowing, while chest irradiation can cause esophagitis, cough, or radiation pneumonitis, and pelvic radiation commonly produces diarrhea, urinary frequency, and sexual or fertility effects. Acute effects typically appear during or shortly after treatment and often improve within weeks to months, whereas late effects—including fibrosis, organ dysfunction (cardiac, pulmonary, renal), cognitive changes after brain irradiation, persistent dry mouth, bone weakening or fracture, and a small increased risk of second malignancies—may emerge months to years later and can be permanent. The severity is influenced by total dose, dose per fraction, volume of normal tissue irradiated, and concurrent systemic therapies, which can amplify toxicity. Modern planning and delivery techniques (IMRT, image guidance, stereotactic approaches, and proton therapy) aim to reduce exposure to normal tissues and lower side‑effect risk, and clinicians use preventive and symptomatic measures—skin care, analgesics, antiemetics, nutritional support, swallowing therapy, pulmonary monitoring, and long‑term surveillance—to manage acute symptoms and detect late complications early. Open communication with the radiation oncology team about expected local side effects, strategies to reduce risk, and signs that require prompt attention helps patients maintain quality of life during and after treatment.

What are the advantages of radiation therapy?

Radiation therapy provides several distinct clinical advantages that make it a cornerstone of cancer care. It is highly effective at controlling or eradicating localized disease, and for many tumor types radiation alone or combined with surgery and systemic therapy can be curative. Because radiation is a local or regional treatment, it can concentrate high doses on the tumor while limiting exposure to the rest of the body, which is particularly valuable when systemic therapies are unsuitable or when organ preservation is a priority. Modern delivery methods—such as intensity‑modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), stereotactic radiosurgery/body radiotherapy (SRS/SBRT), image‑guided techniques, and proton therapy—increase dose precision and reduce collateral damage, lowering the risk of side effects and enabling higher, more effective tumor doses.

Conclusion

Radiation therapy is a precise, local cancer treatment that can cure or control tumors, preserve organs and function, and rapidly relieve symptoms, with modern techniques designed to maximize tumor dose while minimizing harm to healthy tissue.

Read More