Periodontal disease is a spectrum of inflammatory conditions affecting the gums and supporting structures of the teeth, ranging from reversible gingivitis to destructive forms of periodontitis that can lead to tooth loss and systemic health impacts.

What are periodontal diseases?

Periodontal diseases encompass a spectrum of conditions that affect the periodontium—the gingiva, periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone—and arise when bacterial plaque triggers a host inflammatory response that, if unchecked, leads to progressive tissue destruction. At the mild end, gingivitis presents with gum redness, swelling, and bleeding on probing but no attachment or bone loss and is usually reversible with improved oral hygiene and professional cleaning. When inflammation extends into the supporting structures, periodontitis develops: clinical hallmarks include pocket formation, attachment loss, and alveolar bone resorption that can produce tooth mobility and eventual tooth loss. Periodontal disease is multifactorial: plaque and calculus are the primary local drivers, while systemic and behavioral risk factors—most notably smoking, diabetes, certain medications, and immunosuppression—modify susceptibility and progression. Distinct clinical forms exist, including chronic periodontitis, which typically progresses slowly and is common in adults, and aggressive or rapidly progressive forms that affect younger patients and may have familial patterns; necrotizing periodontal diseases represent acute, painful variants linked to severe systemic stress or immunocompromise. Beyond oral consequences, untreated periodontitis has been associated with systemic health implications and can complicate medical conditions, underscoring the need for coordinated care. Diagnosis relies on clinical examination and radiographs to assess pocket depths, attachment levels, and bone loss; management ranges from non‑surgical mechanical debridement and risk‑factor control to surgical therapy and long‑term maintenance for advanced disease. Prevention—regular brushing and flossing, routine dental visits for professional cleaning, smoking cessation, and control of systemic conditions like diabetes—remains the most effective strategy to halt disease onset and progression, preserve dentition, and protect overall health.

What causes periodontal diseases?

Periodontal disease begins when dental plaque, a sticky biofilm of bacteria that accumulates on teeth, provokes inflammation of the gingiva; if plaque and calculus are not removed, the inflammatory response can extend into the supporting tissues (periodontal ligament and alveolar bone), producing pocket formation, attachment loss, and bone resorption.

Plaque‑induced infection is the central driver, but disease expression depends on the balance between microbial challenge and the host’s immune response—some people develop only reversible gingivitis, while others progress to destructive periodontitis.

Behavioral and systemic modifiers play a decisive role: smoking markedly increases risk and severity, and poorly controlled diabetes both raises susceptibility and worsens outcomes.

Certain medications (for example, drugs that reduce salivary flow or cause gingival overgrowth), immunosuppression, and nutritional deficiencies can impair local defenses and healing.

Genetic predisposition and familial patterns explain why some individuals experience rapid or aggressive forms despite similar plaque levels.

Acute variants such as necrotizing periodontal diseases arise when severe systemic stress, malnutrition, or immune compromise combine with pathogenic bacteria to produce painful tissue necrosis.

Effective diagnosis therefore recognizes both the microbial cause and the modifiable risk factors that determine progression and prognosis.

What are the types of Periodontal Disease?

Periodontal diseases comprise a spectrum from reversible gum inflammation to destructive, often systemic‑linked forms of periodontitis; common categories include gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, periodontitis associated with systemic diseases, and necrotizing periodontal diseases.

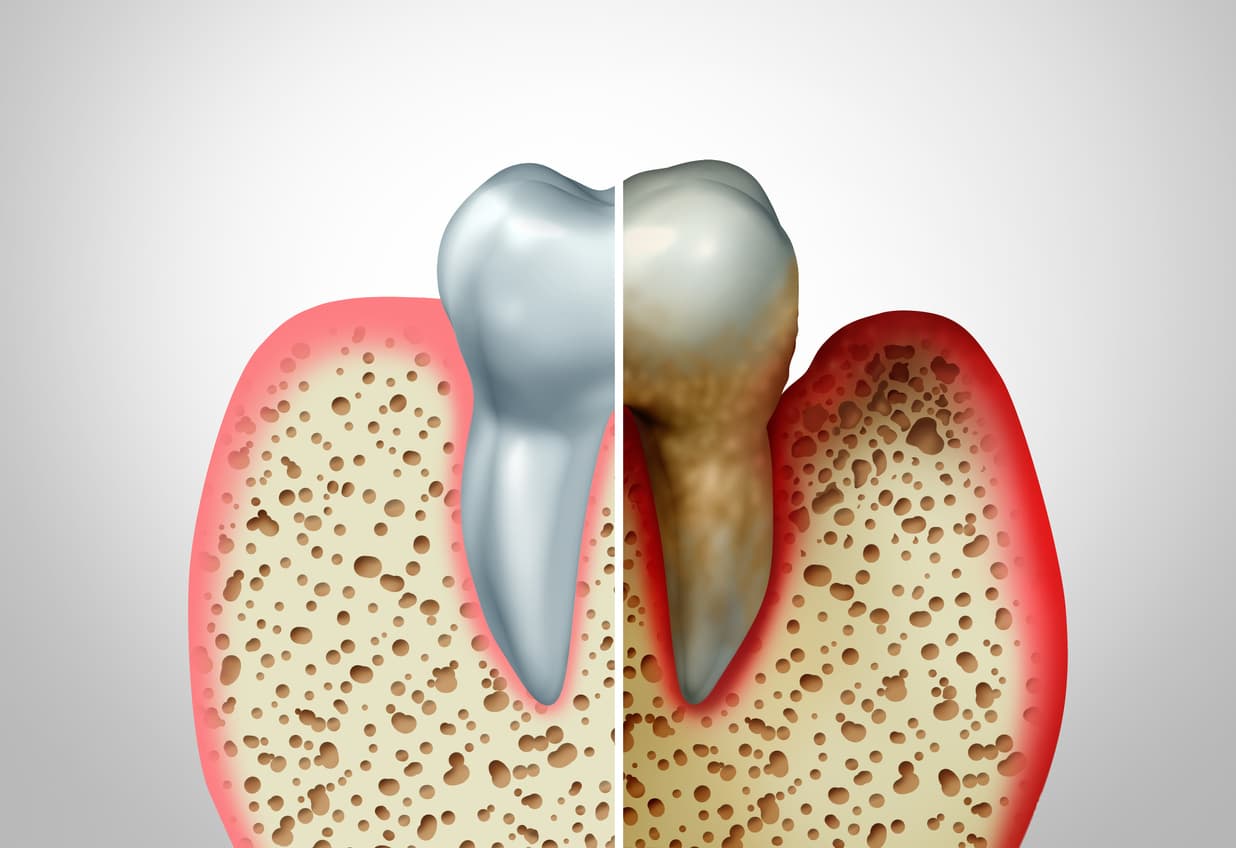

Gingivitis is the mildest, plaque‑driven inflammation limited to the gingiva, characterized by redness, swelling, and bleeding on probing but without attachment or bone loss; it is usually reversible with improved oral hygiene and professional cleaning.

Chronic periodontitis (often simply called periodontitis in modern classifications) is the most prevalent destructive form and features progressive clinical attachment loss, pocket formation, and alveolar bone resorption that may lead to tooth mobility and loss; its course is typically slow to moderate and strongly influenced by local factors (plaque, calculus) and systemic or behavioral modifiers such as smoking and diabetes.

Historically, aggressive periodontitis described rapid attachment and bone loss in otherwise healthy, often younger individuals with familial patterns, but contemporary consensus emphasizes that phenotypic differences reflect variations in rate and extent rather than wholly separate diseases, so cases are now characterized by stage and grade to capture severity and progression risk.

Periodontitis as a direct manifestation of systemic diseases recognizes that hematologic, genetic, or immunologic disorders can produce distinctive periodontal breakdown requiring coordinated medical‑dental management.

Necrotizing periodontal diseases (necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis) are acute, painful conditions marked by interdental papilla necrosis, bleeding, and rapid tissue destruction, typically associated with severe systemic stressors, immunosuppression, or malnutrition and demanding urgent care.

Modern classification frameworks prioritize describing each case by extent (localized vs generalized), severity (staging), and progression risk (grading) to guide therapy and prognosis; treatment ranges from preventive hygiene and non‑surgical debridement for gingivitis and mild periodontitis to combined surgical therapy, antimicrobial strategies, and long‑term maintenance for advanced or rapidly progressing disease, with special attention to modifying systemic risk factors to improve outcomes.

What are the symptoms of periodontal diseases?

Periodontal disease commonly presents with bleeding, swollen or receding gums, persistent bad breath, loose or shifting teeth, and changes in bite or chewing; early signs like bleeding on brushing are reversible, while advanced symptoms indicate attachment and bone loss requiring professional care.

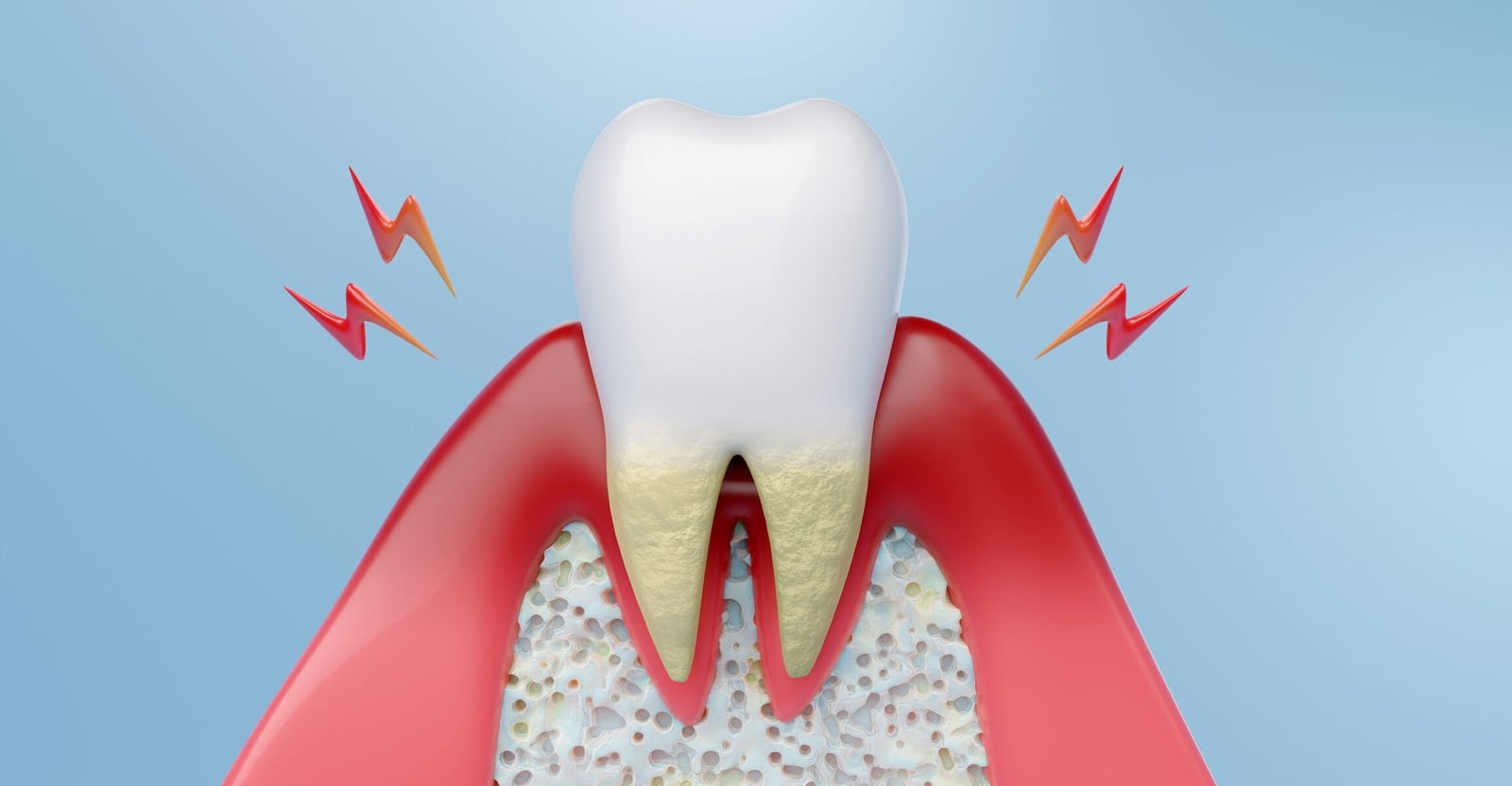

Periodontal diseases produce a range of oral signs that reflect progression from reversible gingival inflammation to destructive periodontitis with loss of supporting tissues.

Early and common symptoms include gum redness, swelling, and bleeding on brushing or flossing, which often signal gingivitis and can be reversed with improved hygiene and professional cleaning.

As disease advances, patients may notice persistent bad breath (halitosis) and a foul taste, both caused by bacterial biofilms and trapped debris in periodontal pockets.

Gum recession and the appearance of longer teeth occur when the gingival margin migrates apically, exposing root surfaces and increasing sensitivity to hot, cold, or sweet stimuli; this can also create esthetic concerns and root caries risk.

Progressive periodontitis produces pocket formation, clinical attachment loss, and alveolar bone resorption, which manifest clinically as tooth mobility, drifting or changes in the way teeth fit together (bite changes), and difficulty chewing.

Acute variants such as necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis or periodontitis present with severe pain, interdental papilla necrosis, spontaneous bleeding, and a grayish pseudomembrane—features that require urgent treatment and are often associated with systemic stressors or immunosuppression.

Importantly, periodontal disease can be painless in early stages, so many people are unaware until more obvious signs (loose teeth or pus from pockets) appear; routine dental exams and periodontal probing are therefore essential for early detection.

Systemic conditions like uncontrolled diabetes and behaviors such as smoking can worsen symptoms and accelerate progression, so patients with risk factors should be monitored closely and counseled on risk modification.

If you experience any of these signs—especially bleeding gums, persistent bad breath, increasing tooth sensitivity, shifting teeth, or pain—seek a dental evaluation promptly to assess pocket depths, attachment levels, and radiographic bone loss so treatment can be started before irreversible damage occurs.

How are periodontal diseases treated?

Treatment begins with thorough diagnosis and risk‑factor assessment, including probing depths, attachment levels, and radiographs to stage and grade disease and identify modifiers such as smoking or diabetes.

The first therapeutic step is non‑surgical mechanical therapy—professional scaling and root planing (deep cleaning) to remove plaque and calculus from supra‑ and subgingival surfaces and to smooth root surfaces so the gingiva can reattach; adjunctive measures may include local antimicrobial delivery or short courses of systemic antibiotics for selected cases with persistent infection or aggressive presentation.

If pockets and inflammation persist despite meticulous non‑surgical care, periodontal surgery is indicated to gain access for debridement, reduce pocket depth, recontour bone, or regenerate lost attachment using bone grafts, guided tissue regeneration membranes, or biologic agents; minimally invasive flap techniques and regenerative procedures aim to restore form and function where possible.

Throughout therapy, control of systemic and behavioral modifiers is essential—smoking cessation, optimized glycemic control for people with diabetes, medication review for drug‑induced gingival changes, and nutritional support for immunocompromised patients all improve outcomes.

After active therapy, patients enter a maintenance phase with individualized recall intervals (commonly every 3 months initially) for professional cleaning, reinforcement of home care, and monitoring for recurrence; long‑term adherence to interdental cleaning, effective brushing, and regular periodontal maintenance is the single most important factor in preventing relapse.

For acute or necrotizing presentations, urgent debridement, pain control, and systemic support are required. Emerging adjuncts—host‑modulation therapies, local sustained‑release antimicrobials, and novel biologics—may benefit selected patients but do not replace mechanical biofilm control.

Successful management therefore combines mechanical therapy, targeted surgical or regenerative procedures when indicated, modification of risk factors, and lifelong maintenance to preserve dentition and reduce systemic health impacts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the major types of periodontal disease—gingivitis, chronic periodontitis, aggressive (rapidly progressive) periodontitis, periodontitis associated with systemic conditions, and necrotizing periodontal diseases—represent variations in location, severity, rate of progression, and underlying systemic influence, not wholly separate illnesses; this means clinical management must be individualized, combining mechanical biofilm control, targeted surgical or regenerative therapy when needed, and modification of systemic and behavioral risk factors such as smoking and diabetes.

Read More