Snoring can often be improved with simple lifestyle changes, oral devices, or positional and airway therapies; if snoring is loud, chronic, or accompanied by daytime sleepiness, seek medical evaluation because it may signal obstructive sleep apnea.

What causes snoring?

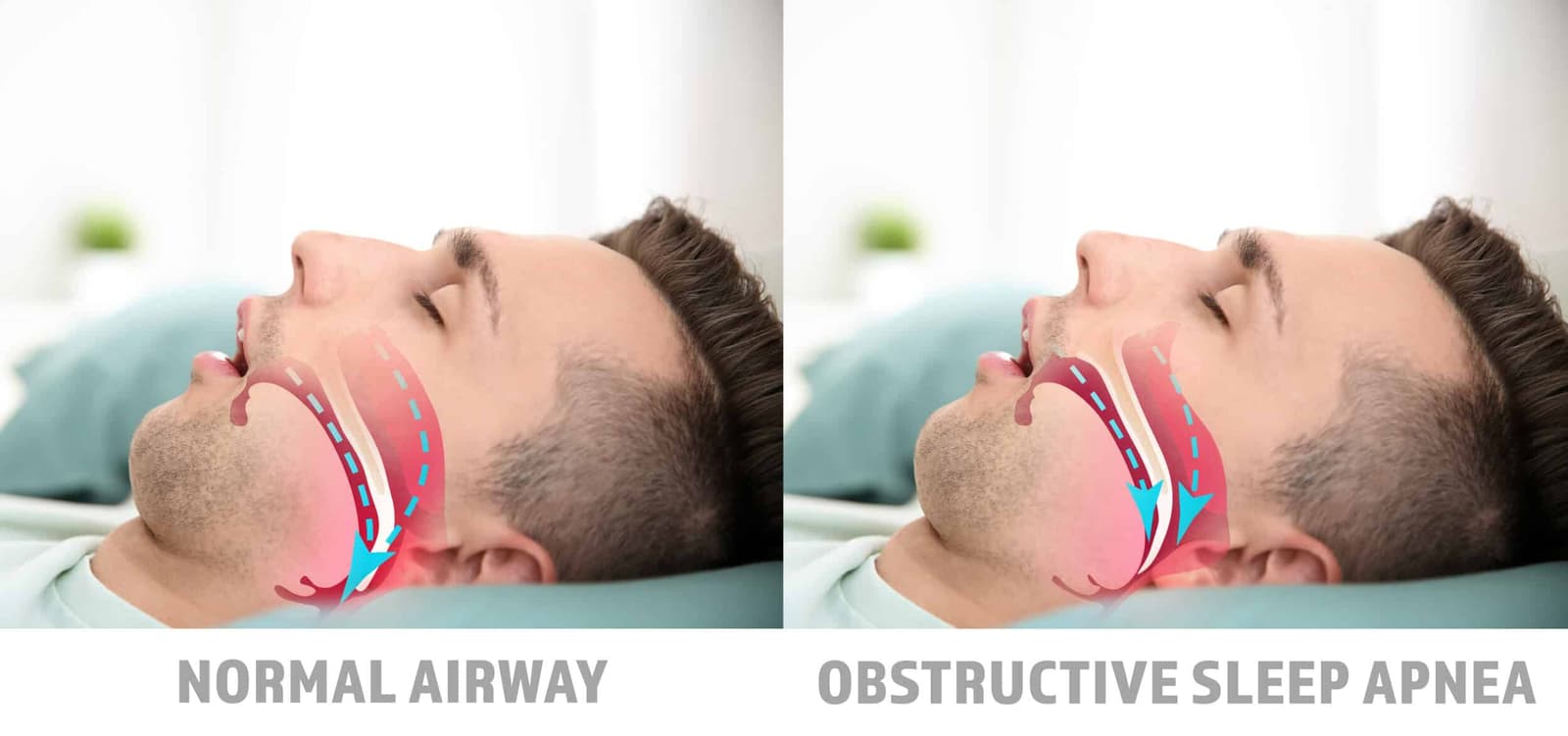

Snoring results from partial obstruction of the upper airway during sleep, which makes relaxed soft tissues — the soft palate, uvula, tonsils, and the back of the tongue — vibrate as air passes through.

Anatomical factors such as a deviated septum, enlarged tonsils or adenoids, a long soft palate, or excess fatty tissue in the neck narrow the airway and increase vibration.

Physiological and behavioral contributors include age-related muscle tone loss, being overweight, sleeping on the back (which lets the tongue fall backward), and use of alcohol or sedatives before bed because they relax throat muscles.

Nasal congestion from allergies or a cold forces mouth breathing and raises the chance of snoring.

In many people, loud habitual snoring is a symptom of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), where the airway repeatedly collapses and briefly stops airflow, causing fragmented sleep and drops in blood oxygen; OSA raises cardiovascular and daytime-sleepiness risks.

Temporary or situational snoring can follow a night of heavy drinking, nasal congestion, or sleeping supine, while chronic snoring more often reflects persistent anatomical or weight-related issues.

Understanding whether snoring is occasional or a sign of OSA guides evaluation and treatment choices.

What are the treatment options for snoring?

Snoring treatment begins with conservative measures that address reversible contributors: weight loss, avoiding alcohol and sedatives before bed, quitting smoking, treating nasal congestion and allergies, and changing sleep position (especially avoiding supine sleep). These steps are low-risk and can substantially reduce mild or situational snoring; clinicians often recommend them as first-line therapy because they target the common physiological drivers of airway narrowing and tissue vibration.

When conservative care is insufficient, oral appliances and positional devices are common next steps. Mandibular advancement devices (MADs), fitted by a dentist, move the lower jaw forward to enlarge the upper airway and are effective for many people with positional or mild obstruction. Positional therapy (vibrating or supportive devices that encourage side-sleeping) helps those whose snoring worsens on the back. Over-the-counter mouthpieces exist but custom devices typically offer better fit and fewer side effects.

For snoring caused by or associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most effective treatment because it splints the airway open during sleep; adherence and mask tolerance are the main challenges. When anatomical problems are identified—deviated septum, enlarged tonsils, or excess soft-palate tissue—surgical or procedural options (nasal surgery, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, radiofrequency ablation, or newer minimally invasive techniques) may be considered after evaluation by an ENT specialist.

Surgical treatments for snoring

Surgical options for snoring—Adenoidectomy, Pillar surgery, and Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP)—are aimed at correcting specific anatomic contributors to airway narrowing; each procedure has distinct indications, expected benefits, recovery profiles, and risks, so careful evaluation by an ENT specialist is essential. Surgical management targets anatomic obstruction that conservative measures cannot fix.

Adenoidectomy removes enlarged adenoids that obstruct the nasopharynx and force mouth breathing; it is most commonly performed in children but can be indicated in adults with clear adenoidal hypertrophy causing nasal obstruction and snoring, and recovery typically involves short hospital stay or same‑day discharge with transient throat pain and nasal congestion; bleeding and infection are uncommon but possible, and symptom relief is often immediate when adenoids are the primary problem.

Pillar surgery (palatal implant or palatal stiffening procedures) places small implants or uses techniques to stiffen the soft palate to reduce its vibration; it is a minimally invasive option for patients whose snoring arises mainly from palatal flutter rather than gross anatomic obstruction, and it usually involves local or general anesthesia with relatively quick recovery, though effectiveness varies and implants can migrate or cause foreign‑body sensation.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), often called throat surgery, removes or reshapes excess tissue from the soft palate, uvula, and sometimes the tonsillar pillars to enlarge the retropalatal airway; UPPP is used for moderate to severe snoring and for selected patients with obstructive sleep apnea when other therapies are unsuitable or as part of multi‑level surgery. UPPP can reduce snoring and apneic events but has variable success rates, potential complications such as persistent throat pain, swallowing changes, velopharyngeal insufficiency, and bleeding, and recovery can be more prolonged than for less invasive procedures.

Which is right for me?

Choosing surgery for snoring begins with diagnosis: determine whether snoring is isolated or part of OSA, and localize the anatomic source (nasal, palatal, tonsillar, tongue base, or multi‑level collapse).

If nasal blockage (deviated septum, enlarged adenoids) is the main problem, nasal surgery or adenoidectomy is often the most direct and effective choice because it reduces nasal resistance and mouth breathing that worsen palatal vibration.

If the soft palate is the primary source of vibration without major OSA, palatal stiffening or palatal implants (Pillar‑type procedures) offer a minimally invasive option with shorter recovery, though results vary and some patients later need additional treatment.

When snoring coexists with moderate–severe OSA or when excess tissue at the oropharynx is the dominant issue, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) or staged multi‑level surgery can be considered, particularly for patients who cannot tolerate CPAP; UPPP removes or reshapes soft‑palate and uvular tissue to enlarge the retropalatal airway but has variable success and a longer recovery profile.

What are the risks?

Surgery for snoring carries general operative risks shared across procedures: bleeding, infection, adverse reactions to anesthesia, and postoperative pain; recovery times vary and some patients require hospital observation or readmission for complications. Even when surgery reduces snoring, results are not guaranteed—many procedures have variable long‑term success and some patients need additional or staged interventions if symptoms persist or recur. These realities make realistic expectations and careful patient selection essential. Procedure‑specific risks differ by operation.

Adenoidectomy, commonly performed in children but sometimes in adults with adenoidal hypertrophy, usually yields rapid symptom relief when adenoids are the primary problem, yet it can cause transient nasal congestion, throat pain, and rare bleeding or infection; very occasionally, persistent nasal regurgitation or velopharyngeal insufficiency occurs.

Pillar surgery or palatal stiffening techniques are minimally invasive and have shorter recoveries, but implants can migrate, extrude, or produce a foreign‑body sensation and effectiveness is inconsistent—some patients ultimately require further treatment.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) and other tissue‑removing throat surgeries carry higher rates of postoperative pain, longer recovery, and specific functional risks such as persistent throat discomfort, altered swallowing, changes in voice or nasal resonance, and velopharyngeal insufficiency; bleeding and infection are also concerns, and success rates for eliminating snoring or obstructive events are variable, especially when multi‑level collapse is present.

Conclusion

Snoring is common and often treatable with lifestyle changes, oral devices, positional strategies, CPAP, or targeted surgery; the best approach depends on the underlying cause, severity, and whether obstructive sleep apnea is present.

Read More