Immunotherapy is a class of treatments that harnesses or modifies the immune system to recognize and attack abnormal cells, especially cancer cells.

What is an Immunotherapy?

Immunotherapy uses the immune system as the active agent rather than relying solely on direct‑acting cytotoxic drugs or radiation: it can stimulate immune cells, remove inhibitory signals that tumors exploit, or introduce lab‑made immune tools to seek and destroy abnormal cells. Major approaches include immune checkpoint inhibitors that block proteins such as PD‑1/PD‑L1 and CTLA‑4 to restore T‑cell activity; adoptive cell therapies (for example, CAR‑T cells) that extract, engineer, and reinfuse a patient’s lymphocytes to target tumor antigens; therapeutic cancer vaccines and oncolytic viruses that prime or amplify anti‑tumor immunity; and monoclonal antibodies and cytokines that either directly target cancer cells or modulate immune signaling to enhance responses. Immunotherapy’s strengths are its potential for durable remissions and the ability to produce systemic, long‑lasting immune memory, but responses vary by tumor type, biomarker status (such as PD‑L1 expression, microsatellite instability, or tumor mutational burden), and individual immune context. Practical decision points include biomarker testing, prior treatments, comorbid autoimmune disease, and access to specialized centers for complex therapies like CAR‑T. Important limitations and risks are immune‑related adverse events (irAEs)—inflammatory reactions that can affect skin, gut, liver, lungs, or endocrine organs—and the fact that not all patients benefit; some may progress despite treatment. Because immunotherapies can require different monitoring, management strategies (including corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants for irAEs), and logistical support, treatment planning typically involves multidisciplinary teams and consideration of clinical trials when standard options are limited.

What happens during immunotherapy?

What typically happens during a course of immunotherapy Patients begin with a baseline evaluation including history, organ‑function tests, and biomarker assays; the care team explains expected timing, possible benefits, and risks. Treatment is given according to the modality: checkpoint inhibitors are usually administered as periodic intravenous infusions; monoclonal antibodies or cytokines may be given IV or subcutaneously; adoptive cell therapies (like CAR‑T) require cell collection, genetic modification and a controlled reinfusion often with short hospital stays. During and after administration, clinicians monitor for immediate infusion reactions and for delayed immune‑related adverse events (irAEs)—inflammatory effects that can involve skin, gut, liver, lungs, or endocrine glands—and treat them promptly with steroids or other immunosuppressants when needed. Response assessment uses imaging and clinical evaluation over weeks to months; some patients show delayed but durable responses while others may not benefit, so ongoing evaluation determines continuation, combination with other therapies, or transition to trials. Long‑term follow‑up includes surveillance for late toxicities, management of chronic endocrine or organ dysfunction if it occurs, and survivorship planning. Multidisciplinary teams coordinate care to balance efficacy, safety, and quality of life throughout the treatment journey.

What are the potential benefits and risks of this treatment?

Immunotherapy can produce durable, sometimes long‑lasting cancer control by harnessing the patient’s own immune system, but it also carries distinct immune‑mediated risks that require careful monitoring. Immunotherapy’s potential benefits include durable remissions, systemic control of metastatic disease, and the ability to generate immune memory that may prevent recurrence; some patients experience dramatic, sustained responses after relatively short courses of treatment. It can be effective where chemotherapy or targeted therapy have failed and may work across multiple tumor sites simultaneously. Risks stem from the immune system’s heightened activity: immune‑related adverse events (irAEs) can inflame organs such as the skin, colon, liver, lungs, and endocrine glands, producing symptoms that range from mild rash and fatigue to severe, life‑threatening organ dysfunction. Specific modalities add unique hazards—CAR‑T cell therapy can cause cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity and often requires specialized inpatient care—while checkpoint inhibitors can trigger autoimmune flares or new autoimmune conditions. Other practical considerations include variable response rates (not all patients benefit), the need for biomarker testing to guide selection, logistical complexity and cost, and the possibility of delayed responses or pseudoprogression that complicate assessment. Early recognition and prompt management of toxicities, multidisciplinary care, and discussion of goals, alternatives, and clinical trials help maximize benefit and reduce harm.

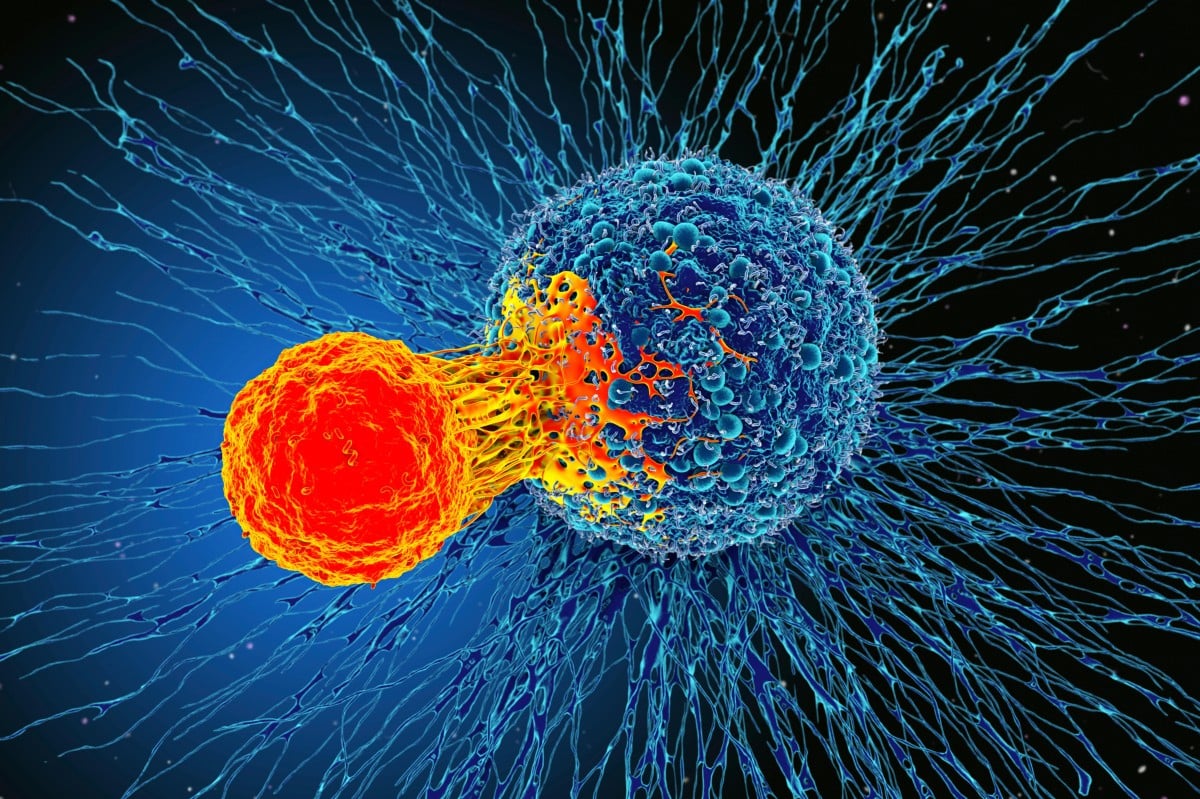

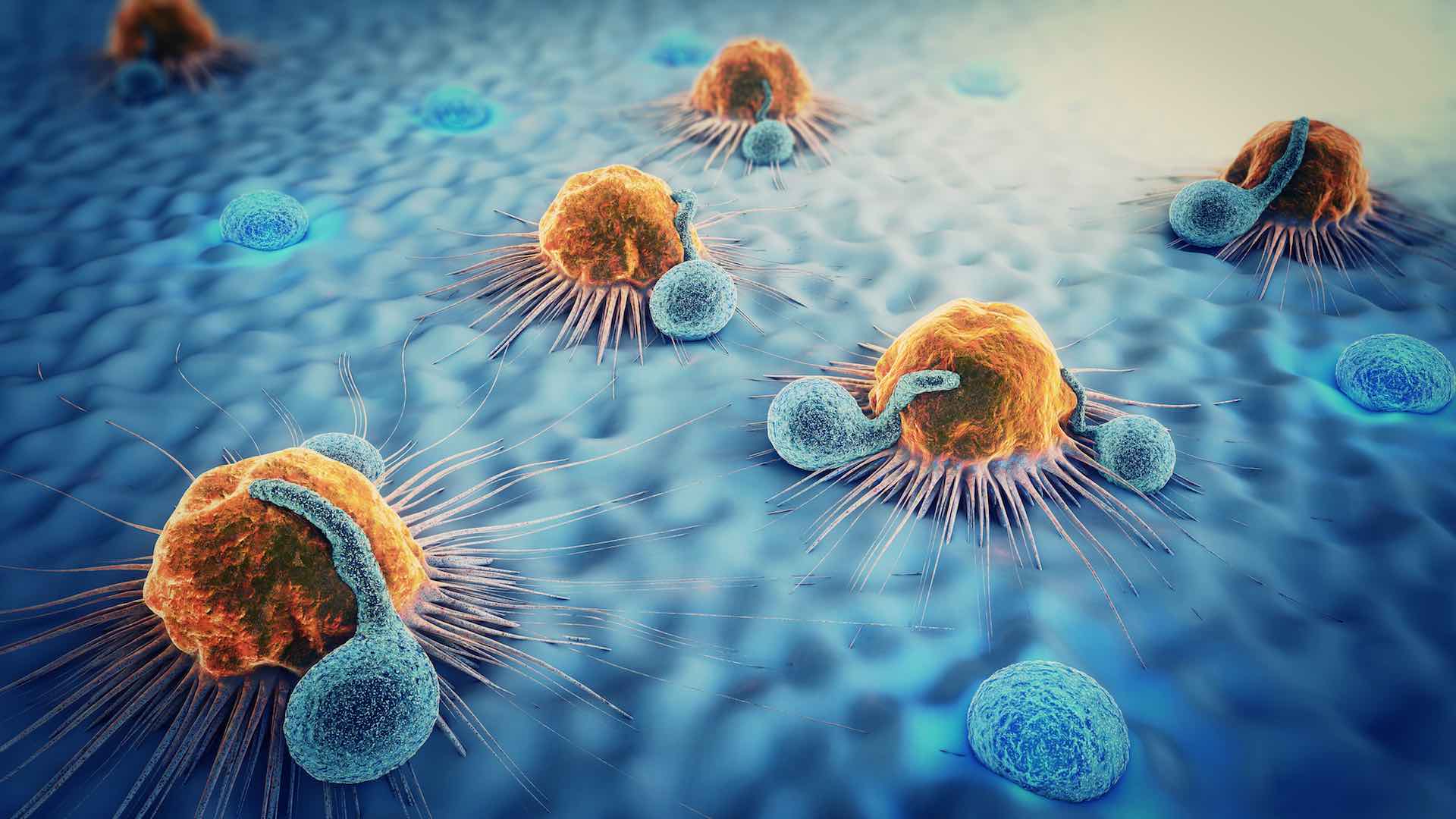

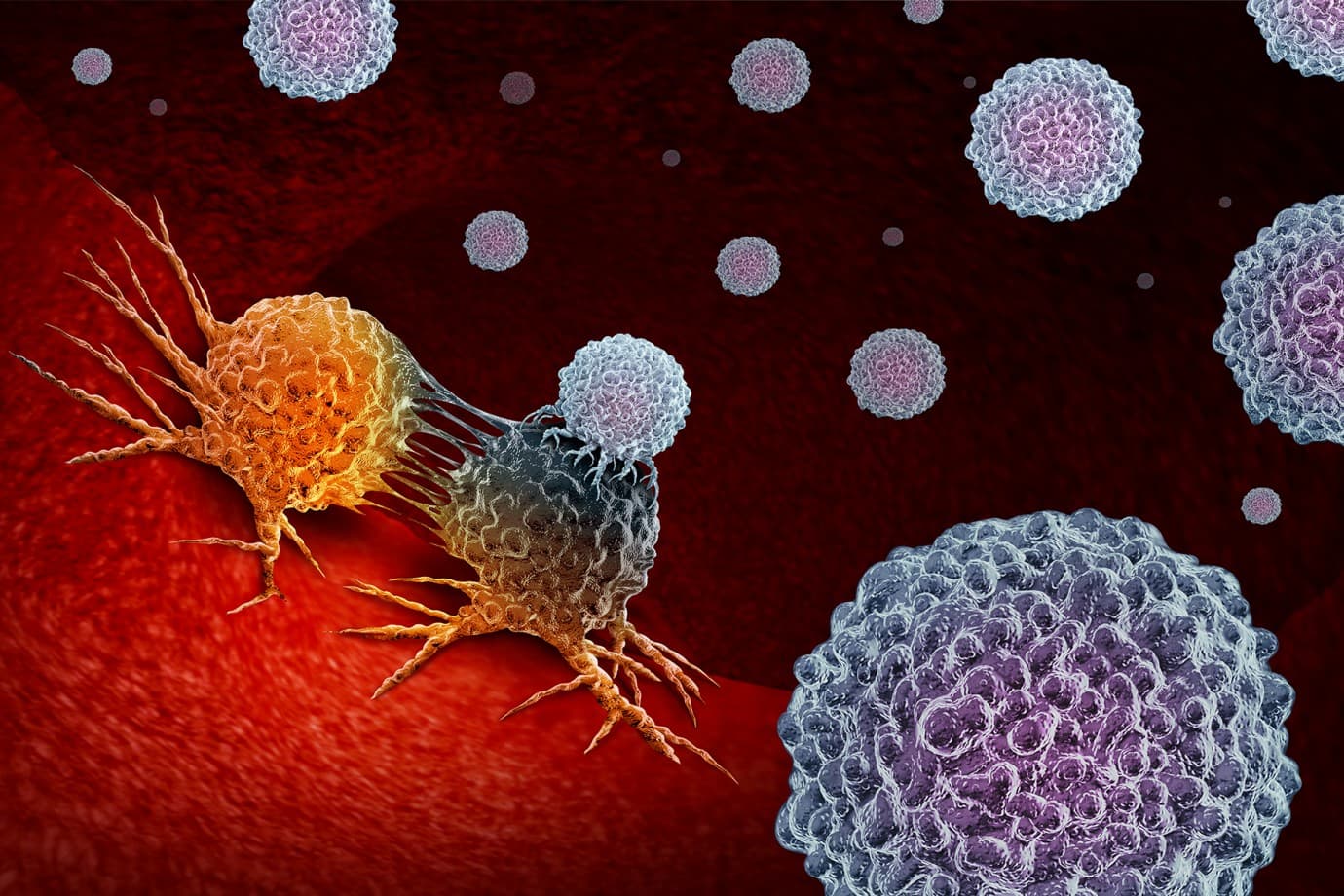

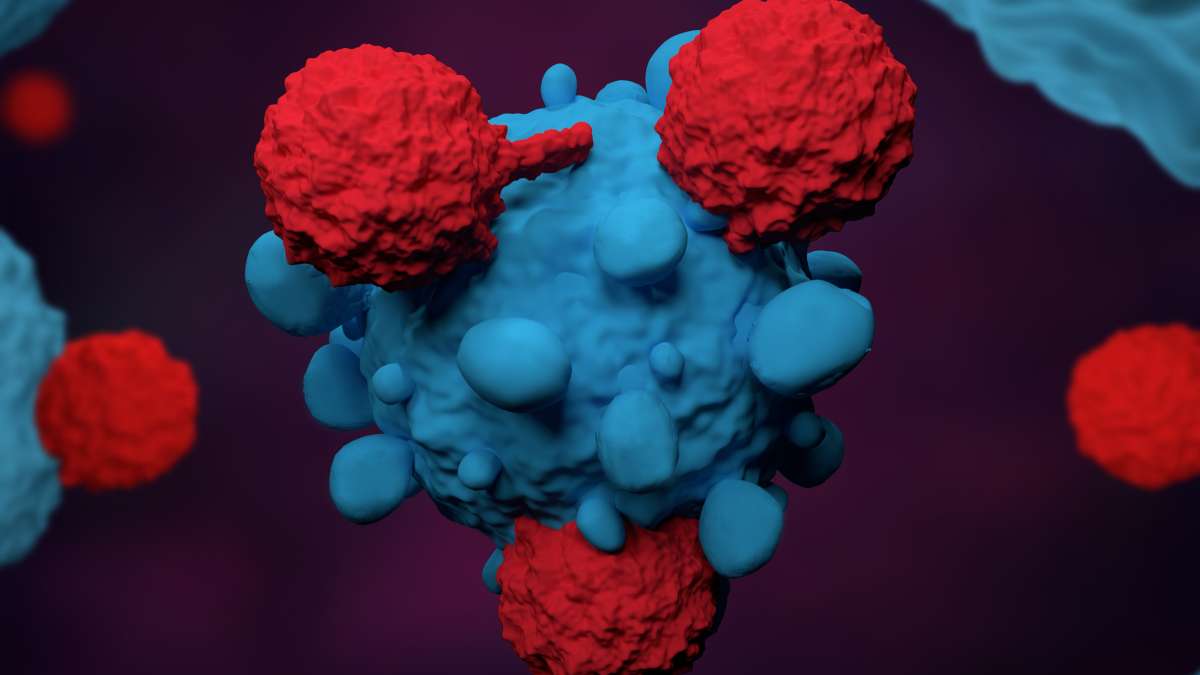

How does immunotherapy affect cancer?

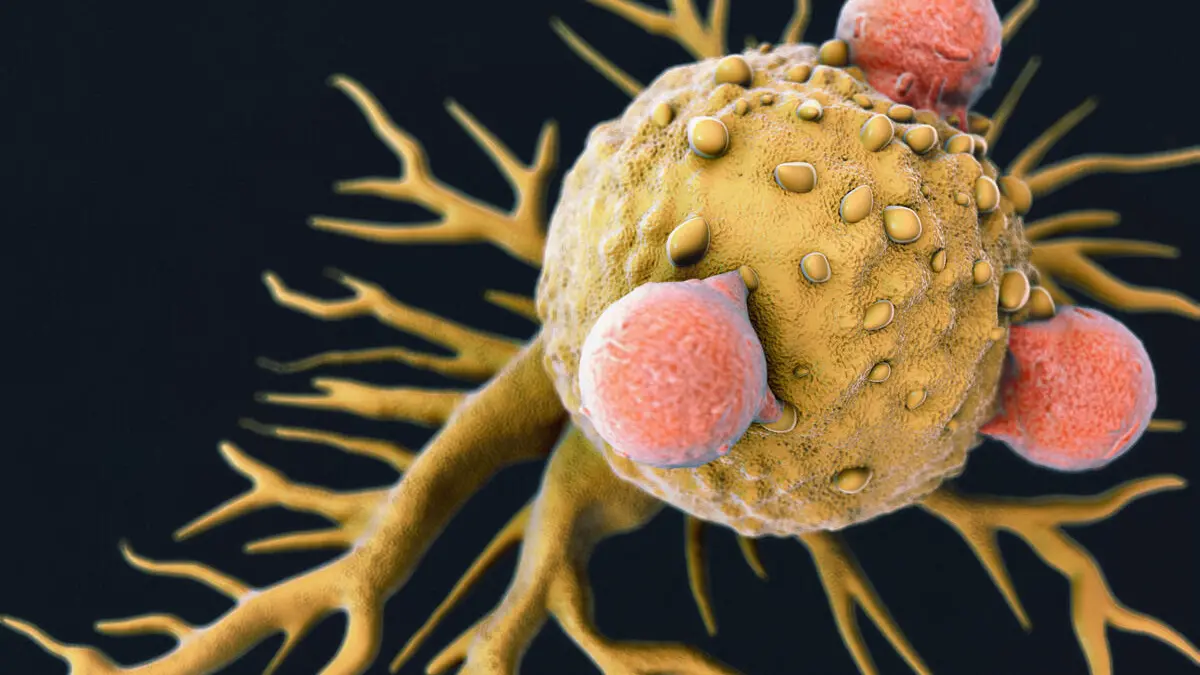

Immunotherapy affects cancer by engaging and reshaping the patient’s immune system to recognize, attack, and sometimes remember tumor cells rather than relying solely on direct cytotoxic effects; different immunotherapies work through complementary mechanisms that can slow, shrink, or eliminate tumors and, in some cases, produce durable remissions. Checkpoint inhibitors release inhibitory signals (for example, PD‑1/PD‑L1 or CTLA‑4 pathways) that tumors exploit to hide from T cells, restoring anti‑tumor T‑cell activity; adoptive cell therapies such as CAR‑T involve extracting a patient’s lymphocytes, engineering or expanding them to target tumor antigens, and reinfusing them to produce potent, targeted cytotoxicity; therapeutic vaccines and oncolytic viruses prime or amplify immune recognition of tumor antigens and can convert “cold” tumors into inflamed, immune‑responsive ones; monoclonal antibodies and bispecifics mark cancer cells for destruction or bridge immune cells to tumors; and cytokine therapies broadly stimulate immune effector functions. These interventions can generate systemic effects that control metastatic disease and establish immune memory, but responses vary by tumor type, antigenicity, and the tumor microenvironment, and they carry risks of immune‑related toxicities that require monitoring and management.

What is the goal of immunotherapy?

The overarching goal of immunotherapy is to empower the patient’s immune system to find and eliminate cancer cells more effectively than it does on its own. Clinically this translates into several specific aims: shrink existing tumors, control metastatic disease, prolong progression‑free and overall survival, and where possible achieve durable remissions or cures by establishing immune memory that prevents relapse. Different immunotherapies pursue these aims through complementary mechanisms—checkpoint inhibitors remove inhibitory signals so T cells can attack tumors, adoptive cell therapies (like CAR‑T) supply engineered immune cells that directly target cancer antigens, vaccines and oncolytic viruses prime or amplify tumor‑specific responses, and monoclonal antibodies or cytokines modulate immune activity or mark cancer cells for destruction. In practice, goals are individualized: for some patients the aim is long‑term disease control with preserved quality of life; for others, especially in early‑stage disease or select hematologic malignancies, the aim may be curative. Importantly, immunotherapy can produce delayed but durable responses and systemic control across multiple tumor sites, but not all patients benefit and responses depend on tumor biology, antigenicity, and the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusion

Immunotherapy represents a transformative shift in cancer treatment by mobilizing or engineering the immune system to recognize and eliminate malignant cells; for many patients it can produce durable, systemic responses that differ fundamentally from the transient cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy. Its success has established new standards of care across multiple tumor types and spurred ongoing research into combinations and biomarkers that broaden who benefits.

Read More