Orthognathic surgery is corrective jaw surgery that realigns the upper and/or lower jaws to improve function (bite, breathing, speech) and facial balance; it’s planned jointly with orthodontics and uses modern 3‑D planning to optimize outcomes.

What is corrective jaw surgery?

Corrective jaw surgery, commonly called orthognathic surgery, is a coordinated surgical and orthodontic approach to fix jaw and facial skeletal discrepancies that cannot be corrected by braces alone. The primary aim is to bring the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandible (lower jaw) into proper alignment so the teeth meet correctly, chewing and speech function improve, and facial proportions become more balanced. Indications include severe malocclusion, facial asymmetry, congenital conditions (such as cleft‑related deformities), trauma sequelae, and functional problems like obstructive sleep apnea or temporomandibular joint dysfunction when conservative measures fail. Treatment is multidisciplinary: an oral and maxillofacial surgeon and an orthodontist collaborate on diagnosis, virtual or model‑based surgical planning, and sequencing of care; patients commonly undergo preoperative orthodontic “decompensation” to align the teeth for surgery, the surgical procedure itself (which may involve Le Fort osteotomy of the maxilla, bilateral sagittal split osteotomy of the mandible, genioplasty, or combinations), and postoperative orthodontics to refine occlusion. Benefits often include improved bite function, airway patency, and patient‑reported quality of life, while risks can include infection, bleeding, sensory changes (notably lower‑lip numbness), relapse, and the potential need for revision procedures. Timing is important: surgery is typically scheduled after skeletal growth has finished, and modern care increasingly uses 3‑D imaging and virtual surgical planning to enhance precision and predictability.

What conditions does Orthognathic surgery treat?

Orthognathic surgery is indicated whenever skeletal rather than purely dental problems underlie a patient’s symptoms and cannot be corrected by orthodontics alone.

The most frequent conditions treated are severe malocclusion (including Class II and Class III skeletal relationships, open bite, and crossbite) where the upper and lower jaws do not meet properly, producing impaired chewing, speech difficulties, excessive tooth wear, or unstable orthodontic results.

Surgeons also correct facial asymmetry and disproportions—vertical maxillary excess, mandibular deficiency or excess, and transverse discrepancies—that affect facial balance and patient self‑image.

Functional airway problems are a major indication: mandibular or maxillary repositioning can relieve obstructive sleep apnea and other sleep‑related breathing disorders by enlarging the pharyngeal airway.

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders with a structural jaw component, congenital and developmental anomalies (for example, cleft‑related deformities), and the long‑term consequences of facial trauma (malunited fractures, bone loss, or asymmetry) are also commonly managed with orthognathic procedures.

In some cases, orthognathic surgery is used to improve outcomes for patients with chronic nasal obstruction or combined airway and occlusal problems.

Because many of these issues affect both function and appearance, treatment is multidisciplinary, typically combining preoperative orthodontic decompensation, virtual or model‑based surgical planning, and postoperative orthodontics to achieve stable occlusion, improved airway function, and enhanced facial harmony.

Types of Orthognathic Surgery

Orthognathic procedures are broadly grouped by the jaw treated.

Upper jaw surgery (maxillary osteotomy) typically involves a Le Fort I osteotomy, which frees the maxilla so it can be moved forward, backward, upward, or downward to correct vertical excess, open bite, or midface deficiency; surgeons may also perform segmental osteotomies to reposition parts of the dental arch or combine maxillary work with surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion (SARME) when transverse deficiency exists.

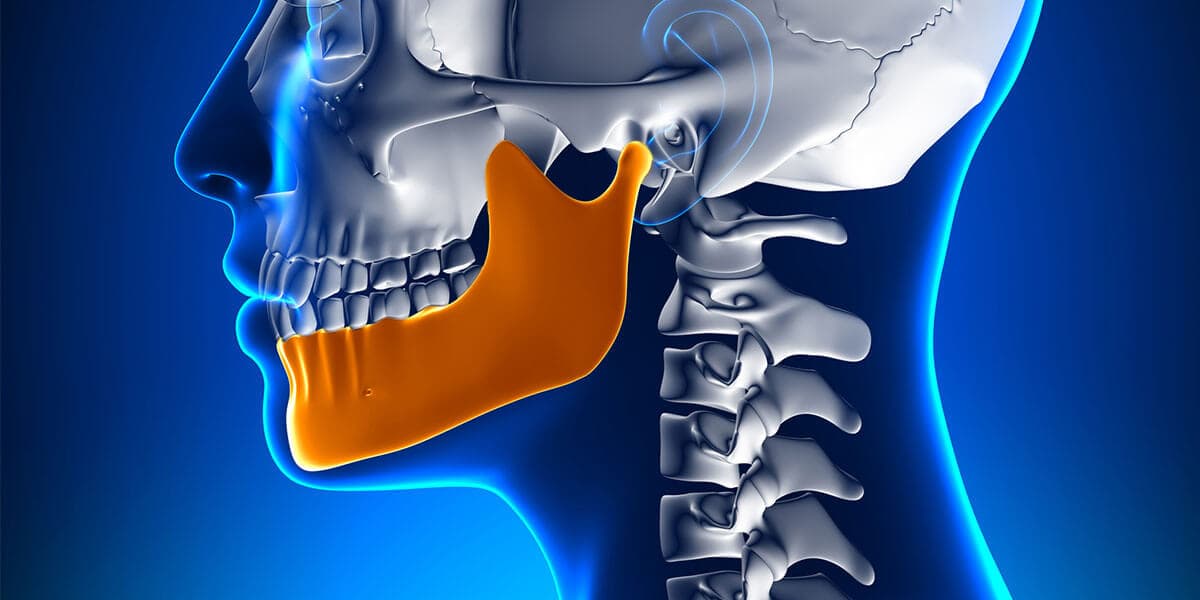

Lower jaw surgery (mandibular osteotomy) most commonly uses the bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) to advance or setback the mandible, correct Class II or Class III skeletal relationships, and restore occlusion; alternative mandibular techniques include intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy (IVRO) for certain setback cases and distraction osteogenesis when gradual lengthening is needed.

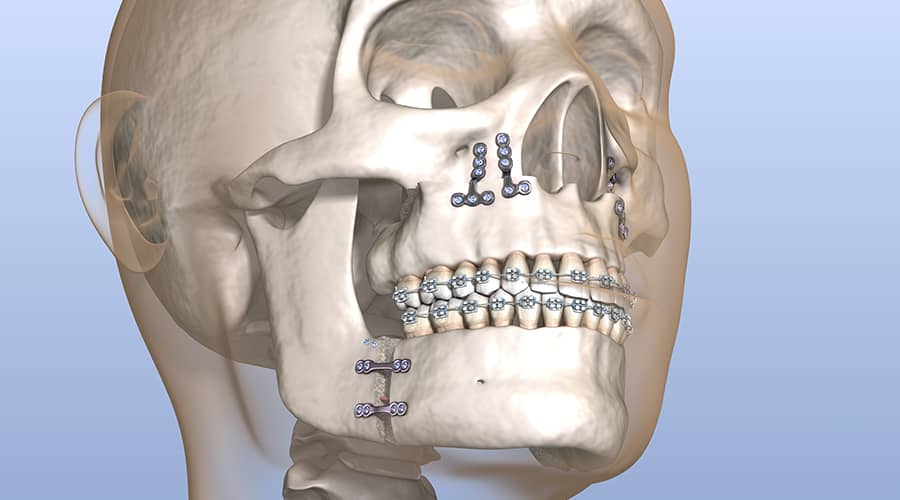

Both jaws may be treated together in bimaxillary surgery when combined repositioning yields better occlusion and facial balance, and genioplasty (chin osteotomy) is frequently added to refine chin projection and lower‑face aesthetics. These osteotomies are performed through intraoral approaches to minimize visible scarring, and fixation uses plates and screws or, less commonly, rigid external devices.

What happens during a jaw surgery?

During corrective jaw surgery you are placed under general anesthesia, the surgeon makes intraoral incisions, performs precise bone cuts to mobilize the jaws, repositions the segments to the planned alignment, and secures them with rigid fixation before you recover in hospital. During the operation the team follows a preoperative plan often created with 3‑D imaging; after induction of general anesthesia the surgeon typically works through the mouth to avoid visible scars, performing osteotomies such as a Le Fort I for the maxilla or a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy (BSSO) for the mandible, or both in bimaxillary cases. Once the jaws are mobilized they are moved into the predetermined position, checked against surgical splints or guides, and fixed with plates and screws; temporary intermaxillary elastics or fixation may be used to stabilize the bite. The procedure usually lasts several hours, with blood loss and nerve handling minimized by careful technique. After surgery patients spend time in recovery and commonly stay in hospital for observation; early postoperative care focuses on pain control, infection prevention, and airway monitoring. Swelling, bruising, limited mouth opening, and a soft or liquid diet are expected, and follow‑up includes wound checks, removal of elastics if used, and continued orthodontic adjustments until final occlusion is achieved.

What are the risks & benefits of Orthognathic surgery?

Orthognathic surgery offers several clear functional and psychosocial benefits: it can restore a stable, efficient occlusion that reduces tooth wear and improves chewing and speech; it often enlarges the airway and can substantially reduce symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea for appropriately selected patients; and it corrects facial skeletal disproportions and asymmetry, which frequently leads to improved self‑image and quality of life. Modern techniques—3‑D imaging, virtual surgical planning, and rigid internal fixation—have increased precision and predictability, shortening operative time and improving postoperative stability. Many centers report high success rates and measurable improvements in function and patient satisfaction after combined orthodontic and surgical care.

However, these benefits must be weighed against known surgical risks:

Common short‑term issues include postoperative swelling, bruising, pain, and temporary limitations in mouth opening and diet; more significant complications can include infection, bleeding, and problems with wound healing. Sensory nerve disturbance—most often numbness or altered sensation of the lower lip and chin after mandibular osteotomies—is a frequent concern and may be temporary or, less commonly, permanent. There is also a risk of skeletal relapse over months to years, which can necessitate orthodontic adjustments or revision surgery; temporomandibular joint symptoms may persist or, rarely, worsen. Less common but serious complications include vascular injury, airway compromise in the immediate postoperative period, and adverse reactions to anesthesia. Because treatment typically spans many months to years (preoperative orthodontics, surgery, and postoperative orthodontic finishing), patients should expect a prolonged recovery and multiple follow‑up visits.

Careful patient selection, thorough preoperative counseling, and multidisciplinary planning reduce risk and improve outcomes, while realistic expectations about recovery time, temporary lifestyle limitations, and the possibility of sensory changes or additional procedures are essential for informed consent.

What happens during Orthognathic surgery recovery?

Corrective jaw surgery recovery typically starts in the immediate postoperative period with close monitoring for airway stability, bleeding, and pain control; patients usually remain in hospital for observation for 24–48 hours or longer if complications arise. Expect marked facial swelling and bruising that peak in the first 48–72 hours and gradually improve over 2–6 weeks, while numbness or altered sensation—especially of the lower lip and chin after mandibular work—may persist for weeks to months and can be permanent in a minority of cases. Early recovery emphasizes airway protection, analgesia, infection prevention, and a soft or liquid diet, with intermaxillary elastics or temporary fixation used selectively to stabilize occlusion. Gradual jaw opening and physiotherapy begin as directed to prevent stiffness; normal speech and chewing return progressively, but strenuous activity and contact sports are restricted for several weeks. Most patients resume light daily activities within 1–3 weeks and return to work or school in 2–6 weeks depending on the extent of surgery and individual healing. Final skeletal consolidation and orthodontic finishing commonly continue for 6–12 months after surgery, and occasional revisions or additional orthodontic adjustments may be needed to optimize function and aesthetics.

Conclusion

Orthognathic surgery can restore functional bite, improve airway and facial balance, and often enhances quality of life, but it requires careful multidisciplinary planning and carries risks such as sensory changes, infection, and possible relapse.

Read More