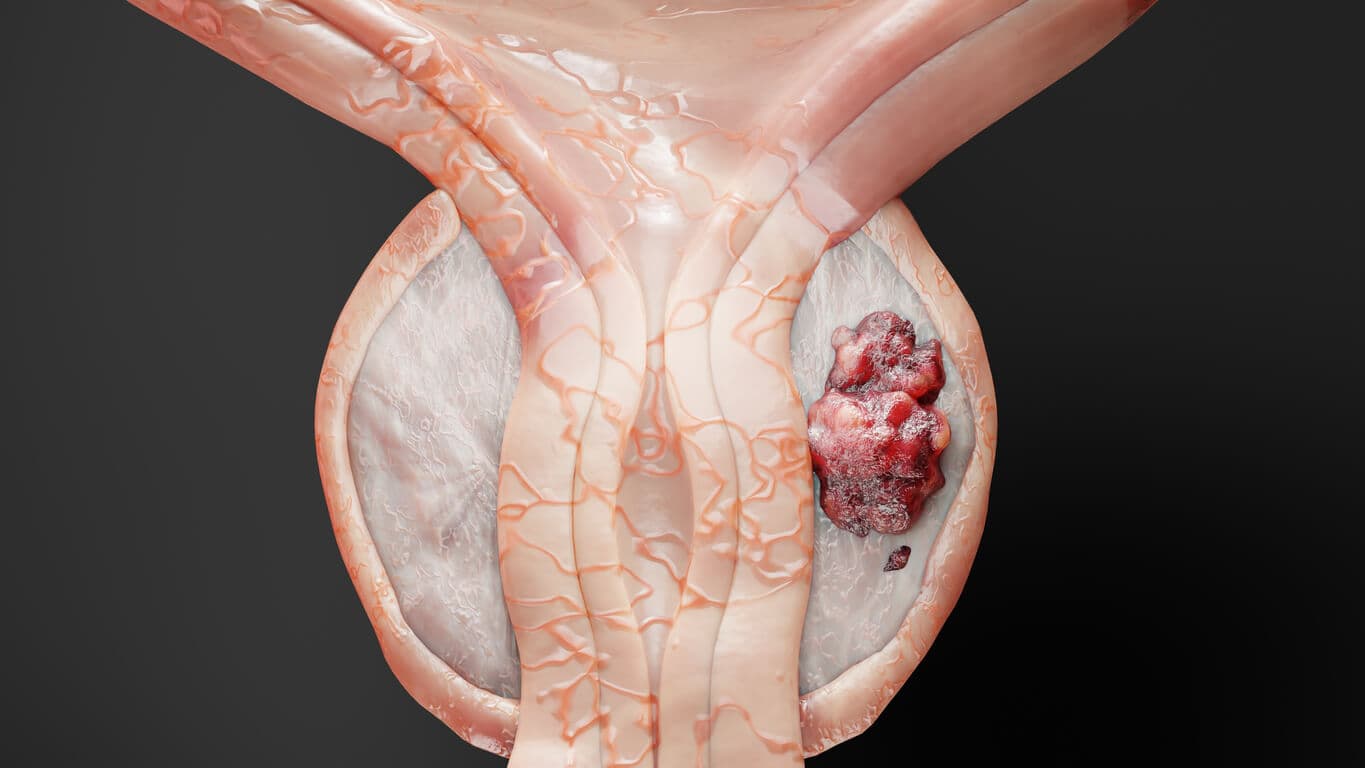

An enlarged prostate, medically called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), is a noncancerous enlargement of the prostate gland that commonly occurs as men age and can compress the urethra or bladder outlet.

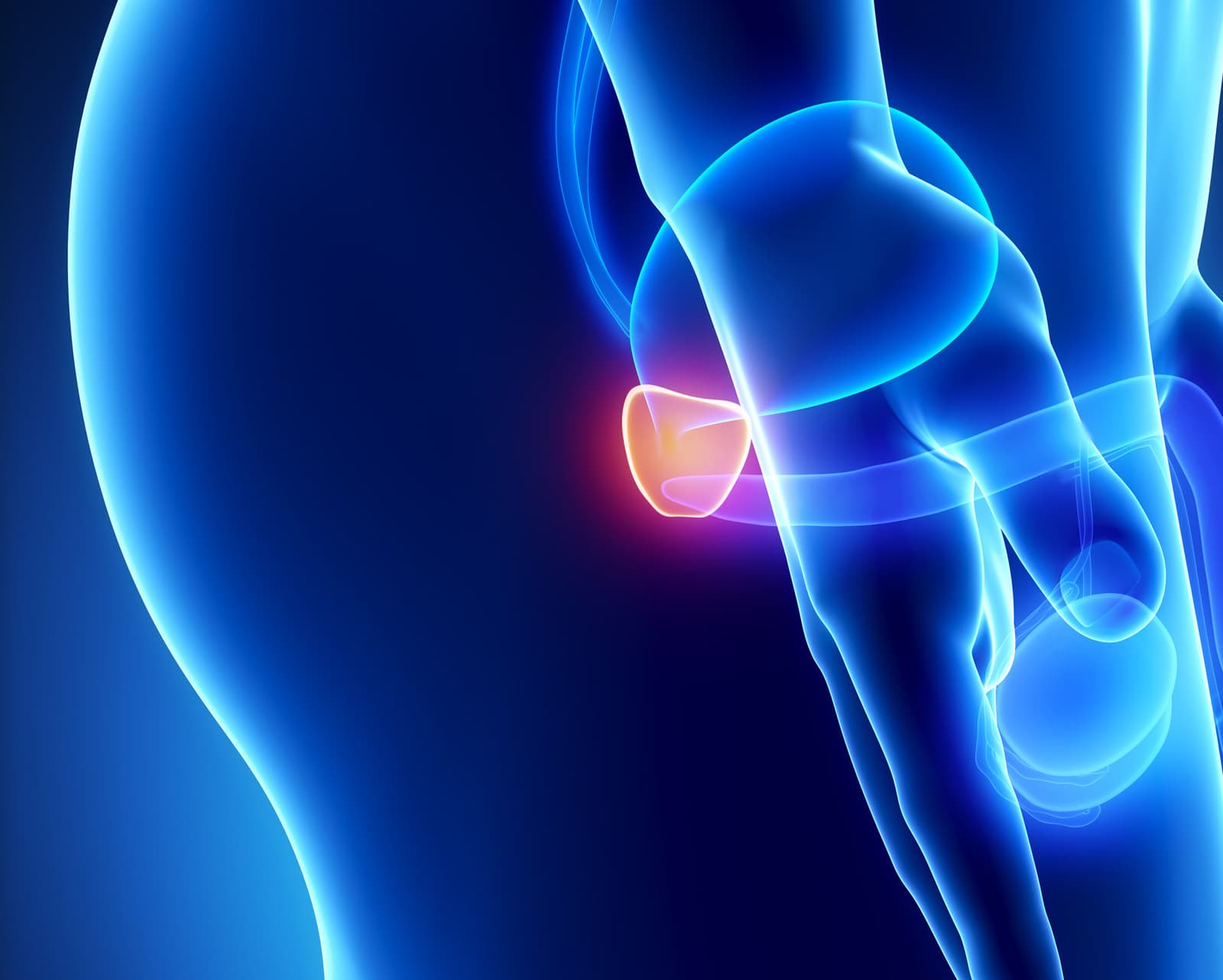

What is the prostate?

The prostate is a small, walnut‑shaped gland that is part of the male reproductive system, situated below the bladder and in front of the rectum with the urethra running through its center; it consists of glandular and fibromuscular tissue and functions primarily to produce and secrete a portion of the seminal fluid that nourishes and transports sperm, while its muscular component helps propel semen during ejaculation. Beyond its reproductive role, the prostate contributes to hormonal regulation in the pelvic environment and influences urine flow because enlargement or structural changes can compress the urethra and bladder outlet, causing urinary symptoms such as weak stream, urgency, nocturia, and incomplete emptying. The gland’s anatomy is described by lobes and zones that relate to where common conditions arise, and it receives blood, nerve, and lymphatic supply that are relevant for disease spread and surgical planning. Prostate health concerns are common with aging and include benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, and prostate cancer, each with distinct implications for symptoms, testing, and management; routine clinical evaluation and appropriate imaging or laboratory tests guide diagnosis and treatment choices.

What is benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common, noncancerous enlargement of the prostate gland that typically develops as men age and can compress the urethra and bladder outlet, producing lower urinary tract symptoms such as weak stream, hesitancy, intermittent flow, urgency, frequency, nocturia, and a sensation of incomplete emptying. The exact cause is not fully understood, but hormone changes, aging, and growth factors appear to drive proliferation of glandular and stromal prostate tissue, and risk is increased by factors such as family history, obesity, diabetes, and lack of exercise. While BPH itself is not malignant, its obstructive effects can lead to complications including urinary tract infections, bladder stones, bladder dysfunction, and, in severe cases, kidney damage. Diagnosis begins with a focused history and physical examination, often including a digital rectal exam and urine tests; additional evaluation may involve prostate‑specific antigen testing, uroflowmetry, postvoid residual measurement, or imaging when indicated.

What are the symptoms of an enlarged prostate gland?

An enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) commonly produces lower urinary tract symptoms that range from mild annoyance to significant disruption of daily life, typically beginning with increased urinary frequency and urgency and a need to urinate more often at night; patients frequently describe a weak or slow urinary stream, difficulty initiating urination (hesitancy), intermittent flow, dribbling at the end of voiding, and a persistent sensation of incomplete bladder emptying. Some people experience straining to urinate or the sudden inability to pass urine, which is a medical emergency. Recurrent urinary tract infections, visible blood in the urine, or the development of bladder stones can complicate longstanding obstruction. Less commonly, longstanding obstruction may lead to bladder dysfunction or kidney problems, signaled by worsening symptoms, flank pain, or reduced urine output. Symptom severity does not always correlate with prostate size, so clinical evaluation typically combines a focused history, physical exam (including digital rectal exam), urine testing, and sometimes flow studies or imaging to determine the cause and guide treatment decisions ranging from conservative management to medications or procedural interventions.

What causes Benign prostatic hyperplasia?

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) arises from a combination of age‑related and hormonal factors that stimulate prostate cell growth, not from infection or cancer; as men age, shifts in sex hormones—particularly a relative increase in dihydrotestosterone (DHT) activity within the prostate and changes in testosterone and estrogen balance—promote proliferation of both glandular and stromal tissue, enlarging the gland and potentially obstructing urine flow. Genetic predisposition and family history influence risk, while metabolic factors such as obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes are associated with increased likelihood and severity of BPH, possibly through inflammatory and hormonal pathways. Chronic low‑grade inflammation within the prostate and local growth factors may further drive tissue hyperplasia. Lifestyle and vascular health also play roles: sedentary behavior, poor diet, and cardiovascular risk factors correlate with higher BPH risk, whereas regular exercise and weight management may be protective. Medication effects and other medical conditions can modify symptoms or the clinical course but are not primary causes. Because prostate size does not always predict symptom severity, evaluation focuses on symptoms, physical exam, and testing to distinguish BPH from other conditions and to guide individualized treatment.

What are the complications of an enlarged prostate?

Enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia) can lead to several complications when left unmanaged, starting with recurrent urinary tract infections from incomplete bladder emptying and progressing to acute urinary retention, a sudden inability to urinate that often requires emergency catheterization; chronic obstruction may cause bladder wall changes and reduced bladder contractility, resulting in persistent incomplete emptying and a weaker stream. Longstanding high bladder pressure can back up into the kidneys, producing hydronephrosis and, in severe cases, impaired renal function or chronic kidney disease. Bladder stones can form from concentrated, retained urine and cause pain, infection, or bleeding. Men may experience hematuria (blood in the urine) related to friable prostatic tissue or associated infections. Sexual dysfunction—including decreased libido, erectile difficulties, or ejaculatory problems—may accompany BPH or arise as side effects of medical and surgical treatments. The cumulative effect of disturbed sleep from nocturia and the psychosocial burden of chronic urinary symptoms can reduce quality of life. Early assessment and individualized management reduce the likelihood and severity of these complications, and patients with worsening symptoms or signs of retention, recurrent infections, hematuria, or impaired kidney function should seek prompt medical evaluation.

What are the treatment options for enlarged prostate glands?

Treatment options for an enlarged prostate span conservative measures, medications, minimally invasive procedures, and surgery, chosen based on symptom severity, prostate size, patient health, and treatment goals. Initial approaches often include lifestyle changes such as reducing evening fluid intake, limiting caffeine and alcohol, timed voiding, and addressing contributing conditions; when symptoms impact quality of life, medical therapy is commonly used with alpha‑blockers to relax bladder neck and prostate smooth muscle for rapid symptom relief and 5‑alpha‑reductase inhibitors to shrink gland volume over months, sometimes combined for greater benefit. Traditional surgical options, notably transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and open or robotic simple prostatectomy for very large glands, remain effective for durable relief but carry higher risks and longer recovery.

Conclusion

An enlarged prostate, or benign prostatic hyperplasia, is a common, noncancerous condition that can significantly affect urinary function and quality of life as men age; early recognition, appropriate evaluation, and individualized treatment—ranging from lifestyle measures and medications to minimally invasive procedures or surgery—allow most men to achieve meaningful symptom relief and reduce the risk of complications. Regular follow‑up with a healthcare provider helps tailor therapy, monitor response, and address side effects or progression, ensuring decisions balance symptom control with preservation of urinary and sexual function.

Read More