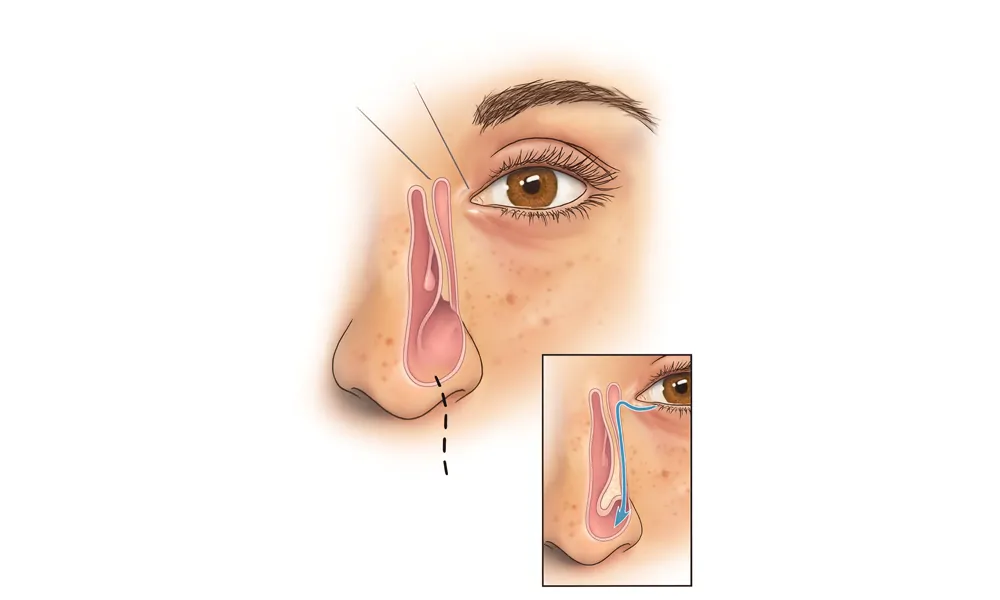

Tear duct surgery (most commonly dacryocystorhinostomy or DCR) creates a new drainage pathway from the lacrimal sac into the nose to relieve persistent tearing, recurrent infections, or chronic discharge.

What is dacryocystorhinostomy?

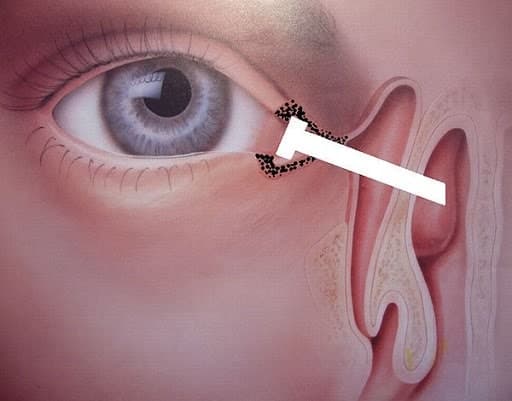

Dacryocystorhinostomy, commonly abbreviated DCR, is a reconstructive procedure that bypasses an obstructed nasolacrimal duct by creating a direct opening between the lacrimal sac and the nasal cavity, allowing tears to drain normally into the nose rather than overflowing onto the face. The operation can be done through a small incision on the side of the nose (external DCR) or entirely through the nasal passages using an endoscope (endonasal or endoscopic DCR), and surgeons often fashion mucosal flaps and remove a small portion of bone to establish a durable connection. A temporary silicone stent may be placed across the new channel to support healing and reduce the risk of early closure; anesthesia and perioperative antibiotics are commonly used, and most patients experience significant reduction in tearing and fewer infections after successful surgery. DCR is indicated for symptomatic obstruction that does not respond to conservative measures such as massage, dilation, or medical therapy, and the choice of technique depends on anatomy, surgeon expertise, and patient priorities.

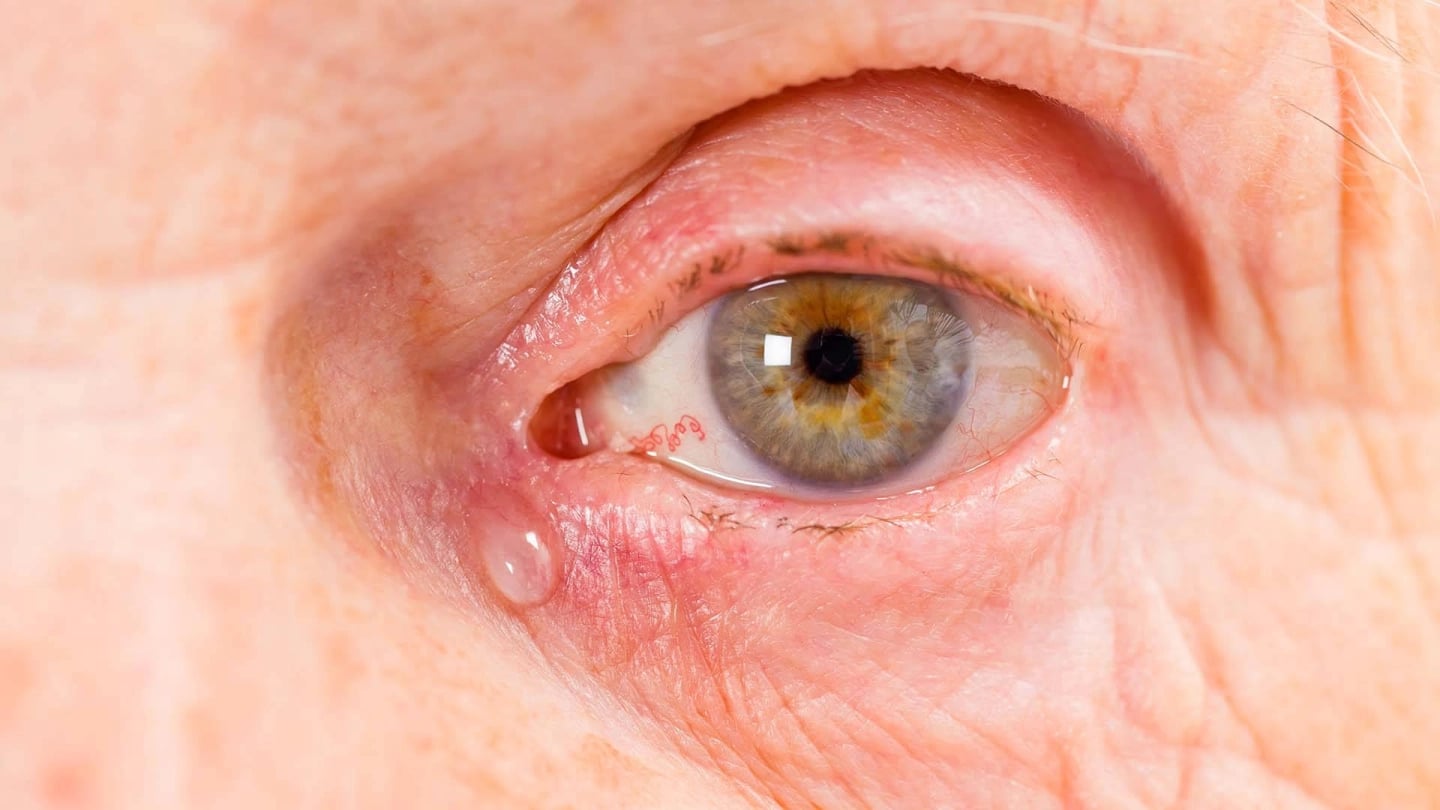

Symptoms of a blocked tear duct

A blocked tear duct typically presents with excessive tearing (epiphora) that causes tears to overflow onto the cheek rather than draining into the nose; this is the hallmark symptom and may be constant or worse with wind, cold, or irritation. Patients often notice mucus or pus discharge, especially on waking, which can lead to crusting of the eyelashes and eyelids and intermittent stickiness around the eye. Recurrent or chronic conjunctivitis (redness and irritation) is common because trapped tears can harbor bacteria, and some people experience blurred vision when the ocular surface is persistently wet. In cases where the lacrimal sac becomes infected (dacryocystitis), there may be tender swelling, redness, and pain at the inner corner of the eye, sometimes accompanied by fever and more purulent discharge; this requires prompt medical attention. Infants with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction typically show tearing and discharge within the first weeks of life and may develop crusting without systemic illness, while adults may develop symptoms after sinus disease, trauma, or age-related narrowing of the drainage system. Symptoms can fluctuate, often worsening after upper respiratory infections or exposure to irritants, and they may significantly affect comfort and daily activities.

Causes of a blocked tear duct

Blocked tear ducts arise from a range of congenital and acquired causes.

In infants the most common cause is a persistent membrane at the valve of Hasner that fails to open at birth, producing congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction; many of these resolve spontaneously within the first year of life with conservative measures such as lacrimal sac massage and hygiene.

In older children and adults, chronic inflammation from recurrent sinusitis or conjunctivitis can scar and narrow the canaliculi or nasolacrimal duct, while acute or chronic infections (including dacryocystitis) can produce obstruction by swelling and debris.

Trauma or facial fractures may disrupt the drainage anatomy, and prior nasal or eyelid surgery can cause iatrogenic narrowing.

Less commonly, nasal polyps, mucoceles, or tumors (benign or malignant) can physically compress or invade the ductal system and produce obstruction.

Age‑related changes such as mucosal atrophy, bony remodeling, or stenosis of the distal duct also increase risk in older adults.

Congenital syndromes and craniofacial anomalies (for example, Down syndrome) raise the likelihood of structural duct problems.

Understanding the likely cause guides management: membranous congenital block often responds to conservative care or simple probing, whereas scarring, mass lesions, or posttraumatic deformity may require imaging and surgical reconstruction.

Different types of DCR procedure

DCR through the skin (external DCR) and endoscopic (endonasal) DCR are two established surgical techniques to bypass an obstructed nasolacrimal duct; external DCR offers direct visualization and slightly higher long‑term success while endoscopic DCR is minimally invasive with no external scar and faster recovery.

External DCR is the traditional approach performed via a small incision on the side of the nose that gives the surgeon direct access to the lacrimal sac and adjacent bone. The surgeon removes a small portion of bone, creates mucosal flaps, and fashions a permanent opening between the lacrimal sac and the nasal cavity; a temporary silicone stent is often placed to support the new channel during healing. External DCR is widely regarded for its excellent visualization and durable results.

Endoscopic (endonasal) DCR is performed entirely through the nostril using a nasal endoscope and specialized instruments, so there is no external incision or visible scar. The surgeon creates the bony ostium and connects the lacrimal sac to the nasal mucosa under endoscopic guidance; concurrent nasal problems (deviated septum, polyps) can be treated at the same time. Advantages include faster recovery and improved cosmesis, while reported success rates are comparable.

Why might I need a dacryocystorhinostomy?

A DCR may be needed for several clear reasons: the most common indication is persistent tearing (epiphora) that interferes with daily life despite medical therapy or lacrimal sac massage, and recurrent or chronic dacryocystitis (infection of the lacrimal sac) that risks repeated pain, swelling, or spreading infection; both scenarios signal that the nasolacrimal duct is obstructed and unlikely to clear without surgery.

Other indications include congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction that does not resolve with conservative infant measures or probing, anatomic narrowing from trauma, prior surgery, or chronic sinus disease, and mechanical compression by nasal masses or tumors that block outflow.

Age‑related stenosis and medication‑related or inflammatory scarring can also produce symptomatic obstruction.

DCR is chosen when imaging or clinical evaluation shows a distal obstruction amenable to bypass and when the goal is durable symptom relief; the procedure can be performed externally or endonasally depending on anatomy, prior procedures, cosmetic concerns, and surgeon expertise. Treating any active infection first and discussing the likelihood of stenting, recovery, and possible need for revision are important parts of deciding on DCR.

Blocked tear duct surgery recovery

After dacryocystorhinostomy, patients commonly experience mild bruising, swelling, and nasal congestion for several days; a pressure dressing or small bandage is often left in place for the first 48 hours and topical ointment or eye drops are used to keep the incision clean and moist. Ice packs applied intermittently during the first 48–72 hours reduce swelling and discomfort. If a silicone stent was placed, it will usually remain for several weeks to months to support the new passage; stent removal is typically performed in clinic about 4–8 weeks after surgery, though timing varies by surgeon and case. Endoscopic DCR patients are commonly instructed to begin nasal douching with saline the day after surgery to clear crust and blood from the operated nostril and to use prescribed nasal sprays as directed to reduce inflammation. Patients should not blow their nose for at least 1–2 weeks, avoid strenuous exercise for about 1–2 weeks, and sleep with the head elevated for the first 48 hours to limit bleeding and swelling. Mild nasal bleeding or crusting is common and can be managed with gentle cleaning; persistent or heavy bleeding, increasing pain, fever, or signs of infection should prompt immediate contact with the surgical team. Vision may be intermittently blurred early on from ointment or tearing, but significant vision loss is uncommon and requires urgent review.

Conclusion

Dacryocystorhinostomy is an effective, well‑established procedure that offers durable relief for patients with symptomatic nasolacrimal duct obstruction. By creating a direct communication between the lacrimal sac and the nasal mucosa, DCR bypasses the diseased or obstructed duct and typically produces substantial improvement in epiphora and a marked reduction in recurrent lacrimal sac infections; success rates are high when the procedure is appropriately selected and performed by experienced surgeons.

Read More